N/A

Select an inline link to view its contents.

As competition for resources in the Arctic Ocean intensifies, nations are staking claims to swaths of undersea territory where oil, gas, and other minerals could someday be found and mined. The United States has just staked its own claim -- and it did so in a way that’s raising lots of questions.

Seventeen years ago, a pair of Russian minisubs whose crew included a prominent polar explorer descended to about 4,300 meters below the surface of the Arctic Ocean. Using a mechanical arm, the crew planted a Russian tricolor flag made of titanium into the seabed and staked claim to hundreds of thousands of kilometers of mineral-rich undersea territory.

“Our dive, our action, was a geographical event, not a political one; it was like planting a flag on Everest or on the moon,” the explorer, Artur Chilingarov, asserted years later.

Others didn’t see it that way. Though it had little scientific significance, the stunt infuriated other Arctic nations and kicked the international rush to map out claims to the seabed into high gear.

Last month, the United States planted its own figurative flag on a huge chunk of Arctic undersea territory, staking out an expanse of seabed twice the size of California. The new U.S. claim covers about 1 million square kilometers in the Beaufort Sea, a windswept expanse stretching hundreds of kilometers north from Alaska’s coastline.

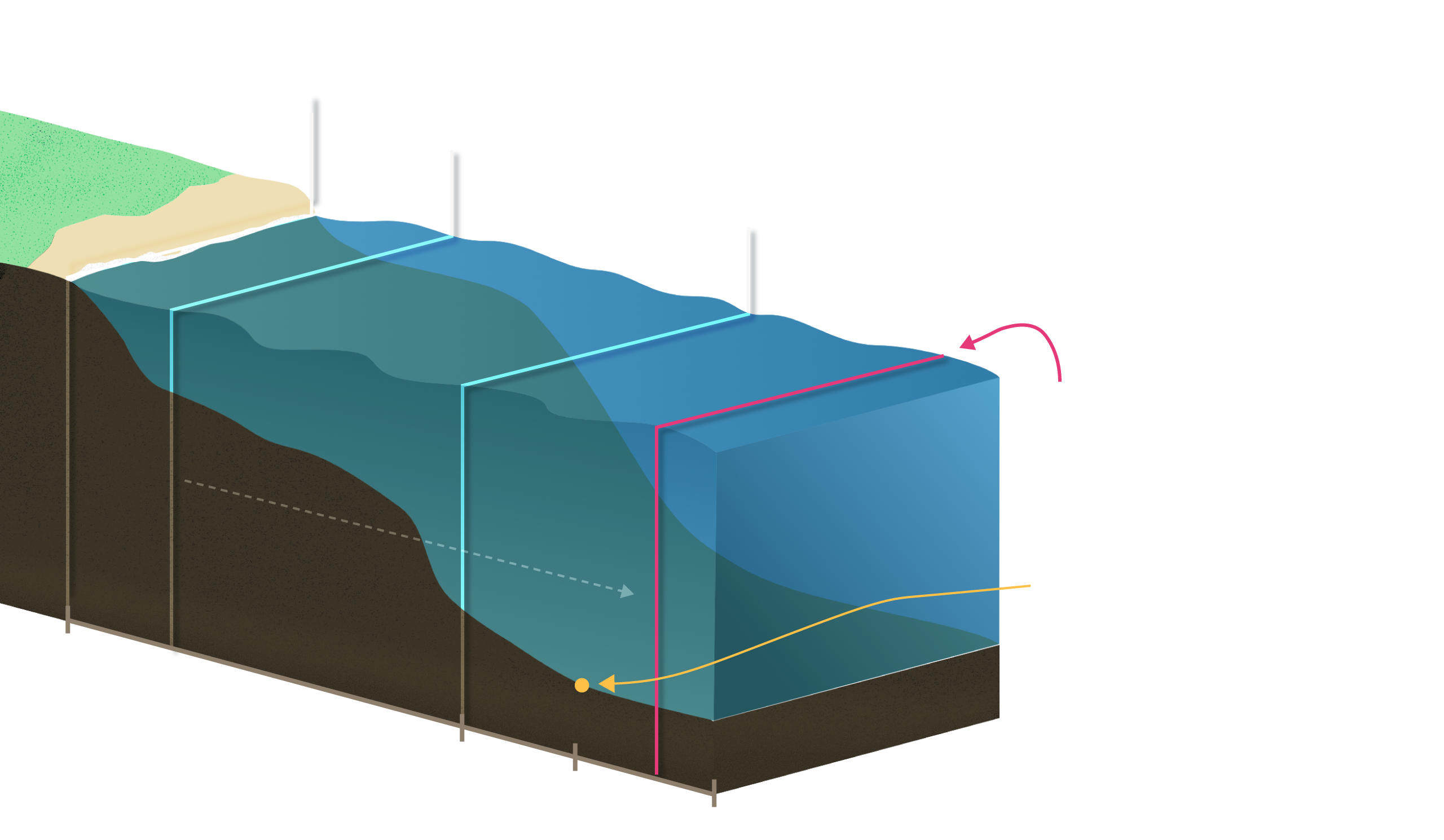

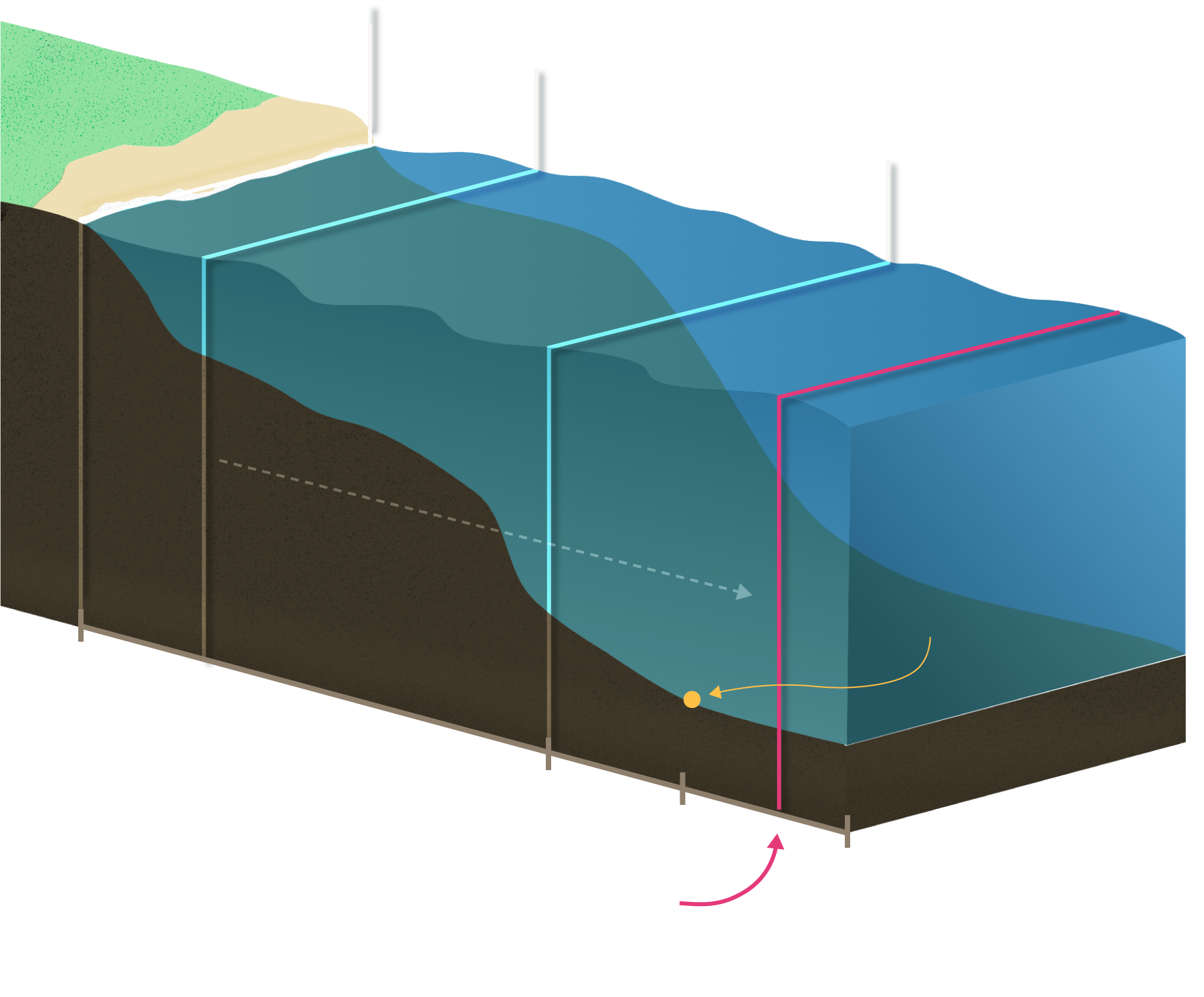

The area the United States is eyeing is what’s called the “extended continental shelf” -- what would essentially be the farthest reaches of U.S. territory under the sea. It could contain huge oil and mineral resources: 90 billion barrels of oil potentially, according to a 2008 report by the U.S. Geological Survey.

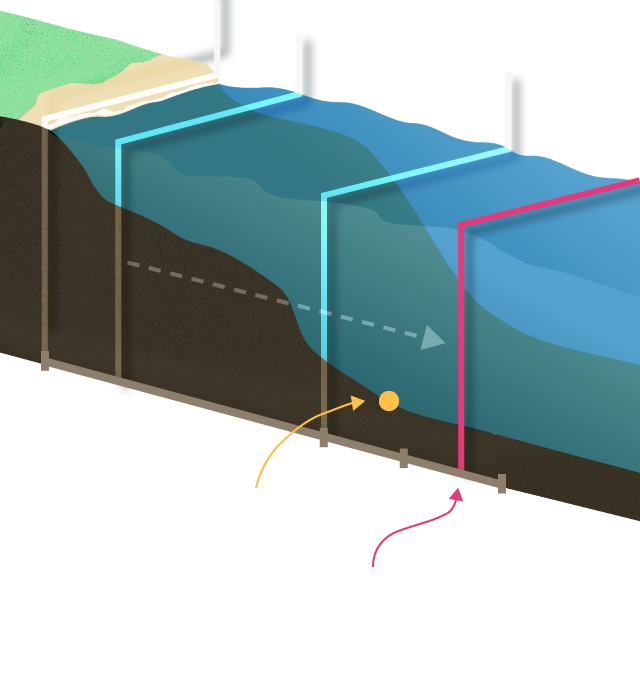

territorial sea

0 - 12nm

exclusive economic zone

from 12nm to 200nm

extended continental shelf

from 200nm

The extended continental shelf ends 350 nautical miles (NM) from the baseline, or 100 nm from the 2,500 meter isobath line, whichever is greater.

continental shelf

Resource rights in ECS regions are

limited to the seabed.

baseline

0 NM

200 NM

300 NM

400 NM

territorial sea

0 - 12nm

exclusive economic zone

from 12nm to 200nm

extended continental

shelf

from 200nm

continental shelf

Resource rights in ECS

regions arelimited to the

seabed.

baseline

0 NM

200 NM

300 NM

400 NM

The extended continental shelf ends 350 nautical miles (NM) from the baseline, or 100 nm from the 2,500 meter isobath line, whichever is greater.

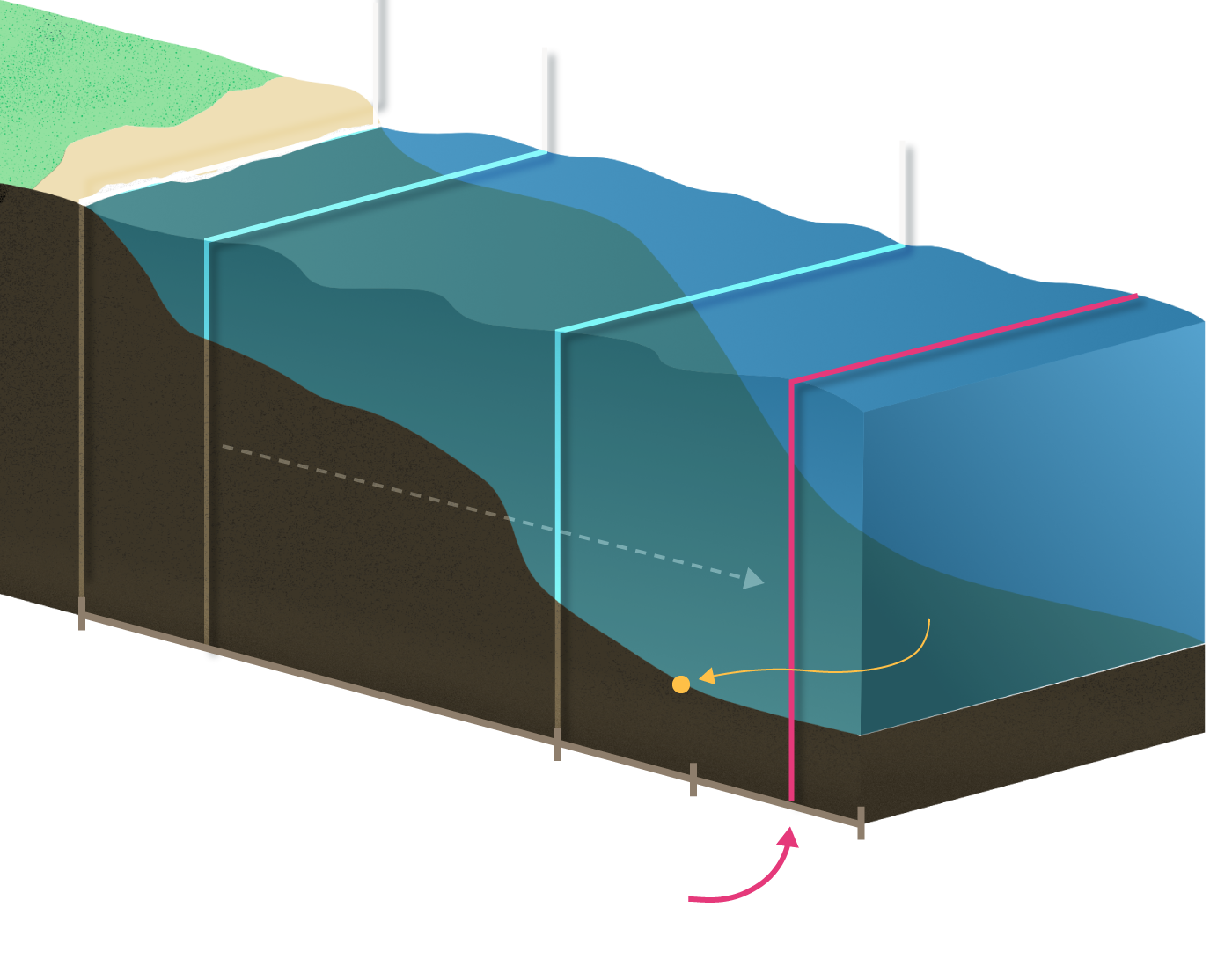

territorial sea

0 - 12nm

exclusive economic zone

from 12nm to 200nm

extended continental

shelf

from 200nm

continental shelf

Resource rights in ECS regions arelimited to the seabed.

baseline

0 NM

200 NM

300 NM

400 NM

The extended continental shelf ends 350 nautical miles (NM) from the baseline, or 100 nm from the 2,500 meter isobath line, whichever is greater.

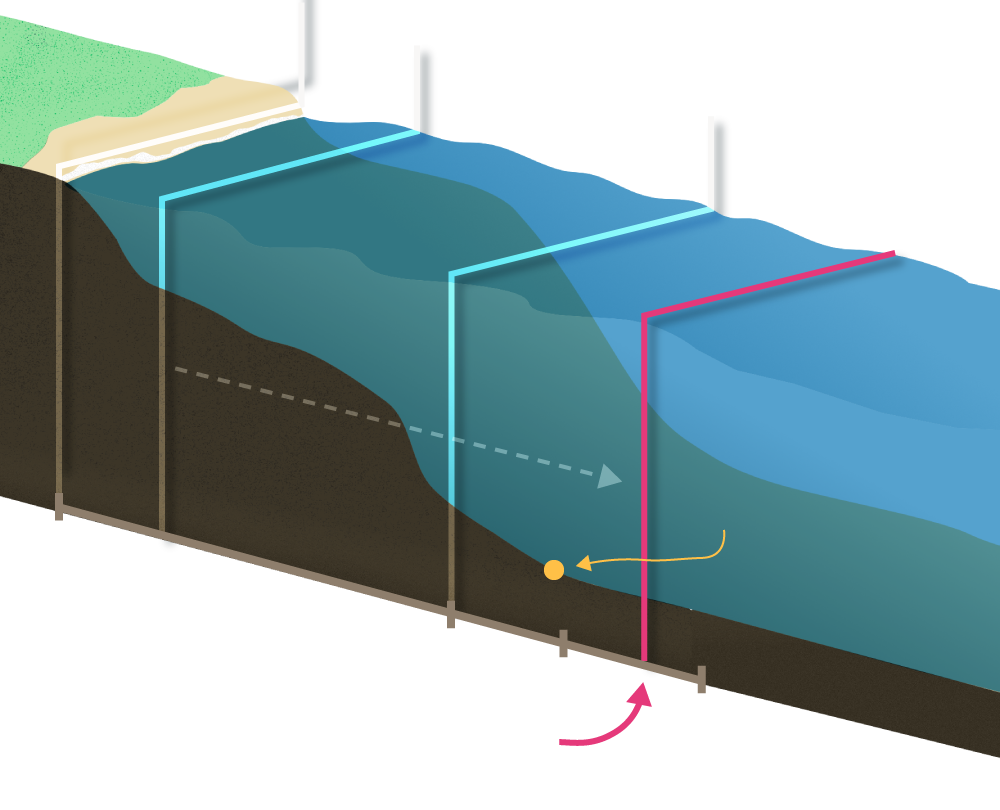

territorial sea

0 - 12nm

exclusive economic zone

from 12nm to 200nm

extended continental

shelf

from 200nm

continental shelf

Resource rights in ECS regions arelimited to the seabed.

baseline

0 NM

200 NM

300 NM

400 NM

The extended continental shelf ends 350 nautical miles (NM) from the baseline, or 100 nm from the 2,500 meter isobath line, whichever is greater.

territorial sea

0 - 12nm

exclusive economic zone

from 12nm to 200nm

extended

continental

shelf

from 200nm

continental shelf

baseline

0 NM

200 NM

300 NM

400 NM

Resource rights in ECS regions are limited to the seabed.

The extended continental shelf ends 350 nautical miles (NM) from the baseline, or 100 nm from the 2,500 meter isobath line, whichever is greater.

Other countries have done the same thing for their “extended continental shelf.” Russia, for example, has submitted several claims under a process sketched out by a 1994 UN treaty called the Convention on the Law of the Sea. Among other things, the treaty, known widely by its acronym UNCLOS, set up a way for countries to collect evidence, make a territorial claim, and have the claim reviewed by scientific experts.

But while Russia is a member of UNCLOS, the United States isn’t. The announcement made by the U.S. State Department last month essentially boils down to this: If we were ever part of the treaty, which may or may not happen someday in the future, then this is what our claim would look like.

“It was a very unconventional and surprising move,” said Rebecca Pincus, director of the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C.

“As the kids would say, it’s a choice, because yes, the U.S. has claimed a million square kilometers of territory, which is great, but we have done so in a way that raises some questions about international law,” she said in an interview.

The U.S. perspective is, “‘We’re not staking a claim, we’re merely registering, we’re declaring the limits of what is ours by nature of geology, rather than through some sort of political flag-planting, as it were,’” said Philip Steinberg, a political geographer and head of the Center for Borders Research at Durham University in Britain.

Russia Plants Its Flag

In 2007, two Russian minisubs planted a titanium flag at the North Pole at a depth of 4,300 meters below the surface of the Arctic Ocean, setting off a rush to stake out claims to the seabed.

The U.S. Lays Claim To The Arctic

In December 2023, the U.S. claimed about 1 million square kilometers in the Beaufort Sea, overlapping Canadian claims in the same area.

The U.S. Bering Sea Claim

The U.S. also claimed 176,300 square kilometers in the Bering Sea, but this claim does not cross the U.S.-Russia maritime boundary set by a 1990 treaty.

Russia's Latest Claim

Russia's claim to the Arctic seabed has evolved and enlarged over the years since its first submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in 2001. Following its latest revision in February 2023, the claim covers an area of about 2.1 million square kilometers.

Canada, Norway, and Denmark

The other three Arctic nations all have their own claims, with the Canadian, Russian, and Danish claims overlapping each other over an area covering much of the Arctic Ocean.

Arctic Ocean

Out of an area of approximately 2.8 million square kilometers located outside of the Arctic nations' exclusive economic zones, only about 18,000 square kilometers, or less than 1 percent, remain unclaimed.

For its part, the United States spent nearly two decades mapping and exploring before finalizing its claim, publicly released on December 19: “The largest offshore mapping effort ever conducted by the United States.”

The claim extends north, toward the North Pole, away from the “exclusive economic zone.” It’s located entirely in the Beaufort Sea and includes the undersea formations known as the Beaufort Shelf and the Beaufort Slope. It also includes part of a formation called the Chukchi Shelf and the Chukchi Borderland. It does not include any claim to territory west of a maritime boundary that the United States and the Soviet Union agreed on in 1990.

In Russia, the U.S. move was met with skepticism, if not hostility.

“The unilateral expansion of borders in the Arctic is unacceptable and can only lead to increased tensions,” Nikolai Kharitonov, a lawmaker who heads the Russian parliament’s Arctic committee, told RIA Novosti. “Before anything, it’s necessary to prove the geological affiliation of these territories, as Russia did in its own time.”

Neither Denmark nor Norway responded to requests for comment. A spokeswoman for Canada’s Foreign Ministry said in an e-mail: “The government of Canada will continue its efforts to obtain international recognition of the outer limits of Canada's extended continental shelf. Canada and the U.S. are in frequent communication with regards to the continental shelf in the Arctic, and have expressed their commitment along with other Arctic states to the orderly settlement of overlapping claims.”

In its announcement justifying the claim, the U.S. State Department said that Washington had “strongly supported” the treaty and that “it has been the policy of the United States to act in a manner consistent with its provisions with respect to traditional uses of the ocean.”

Asked for further response to the criticism of the U.S. position, a State Department spokesperson said UNCLOS reflected “customary international law” -- a legal concept that basically says if a general practice or norm is widely accepted by nations and consistent and recognized over time, then it essentially amounts to a law.

“Like past administrations, both Republican and Democratic, this administration supports the United States joining the Law of the Sea Convention,” the spokesperson said in an e-mail. “The United States has consulted widely with UNCLOS parties on this matter and will continue to do so. Our approach is inclusive and transparent.”

Elizabeth Buchanan, an expert on polar geopolitics with the Modern War Institute at the U.S. Military Academy in New York, called the U.S. claim “somewhat schizophrenic.”

“This erodes credibility of an international system the West has worked tirelessly to achieve, promote, and protect.”

“It appears to be a political signal with no clear direction or intention beyond clarifying there is a thinning line between customary law and American exceptionalism,” she told RFE/RL in a text message. “This erodes credibility of an international system the West has worked tirelessly to achieve, promote, and protect.”

Pincus echoed the notion that the claim was consistent with the treaty.

“But yeah, at the same time, it's what our competitors are saying. You look at the Russian coverage of this and it's once again, ‘The United States is not playing by the rules that, you know, everyone wants everyone else to follow,’” she said. “There is certainly that interpretation out there.”

Also raising eyebrows among Arctic experts and cartographers: the fact that Washington justified the announcement by citing a treaty clause -- Article 76 -- which it said allowed the United States to submit the claim to the UNCLOS commission even though it is not part of UNCLOS.

For example, when countries submit technical data to the commission, Steinberg said, the understanding is that the commission will review them -- a peer-review process, essentially.

“I do see where Russia has a perspective to say, ‘How do we know’ the U.S. claims are valid?” he said. “That said, I wouldn’t say necessarily it’s an inherently belligerent act.”

The claim, Pincus said, highlights “how political paralysis in Congress is impacting the U.S. ability to be effective or lead in the Arctic.”

“While Russia is pouring billions of dollars into building out Arctic infrastructure, and building yet more icebreakers to add to its fleet, already the world’s largest, the United States is unable to confirm ambassadors for Arctic affairs, or vote on UNCLOS, or even allocate money to update [the] over-the-horizon radar station,” she said.

“From a State Department perspective, this is something that they can do, they can get this announcement out there, and I kind of get it,” she added. “You can sort of understand why they would say, ‘Well, it seems like we might as well just put this out there. You know, in the meantime, because it seems very unlikely that we're going to get UNCLOS ratification anytime soon.”

Credits

Written by Mike Eckel. Reported by Mike Eckel, Wojtek Grojec, Ivan Gutterman. Designed by Wojtek Grojec, Ivan Gutterman. Edited by Steve Gutterman. Video: Shutterstock, continental shelf claims data from maps by IBRU, Durham University, U.K.