August 10, 2018

Fifty years ago, the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia killed more than 100 people and shattered that country’s attempts to reform communist rule.

Now, you can stand in the footsteps of the Czechs and Slovaks who snapped the most iconic images of those momentous midsummer days.

Double tap/click, or use the slider to transition between before and after images.

A rally on Prague's Old Town Square in February 1968 to mark the 20th anniversary of the socialist coup. CTK Photo/Karel Mevald

Czechoslovakia, a socialist republic since a Soviet-backed, Communist-led coup in 1948, had remained relatively prosperous but still suffered under Soviet domination.

A massive granite monument to Stalin and socialism towered over Prague until its demolition during de-Stalinization in 1962. Public Domain

By the 1960s, thousands of Czechs and Slovaks had been imprisoned or otherwise persecuted for their politics, including through show trials and executions. Under Stalin and his successors Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev, Czechoslovakia was a nation living in fear.

Communist Party leader Alexander Dubcek arriving for a session of parliament months after the invasion that would retroactively permit Warsaw Pact troops on Czechoslovak soil. Jovan Dezort(CTK)

In January 1968, Alexander Dubcek (center) took leadership of Czechoslovakia's Communist Party. The grinning Slovak announced plans to ease censorship and restrict the powers of the hated secret police. Dubcek vowed to create “socialism with a human face.”

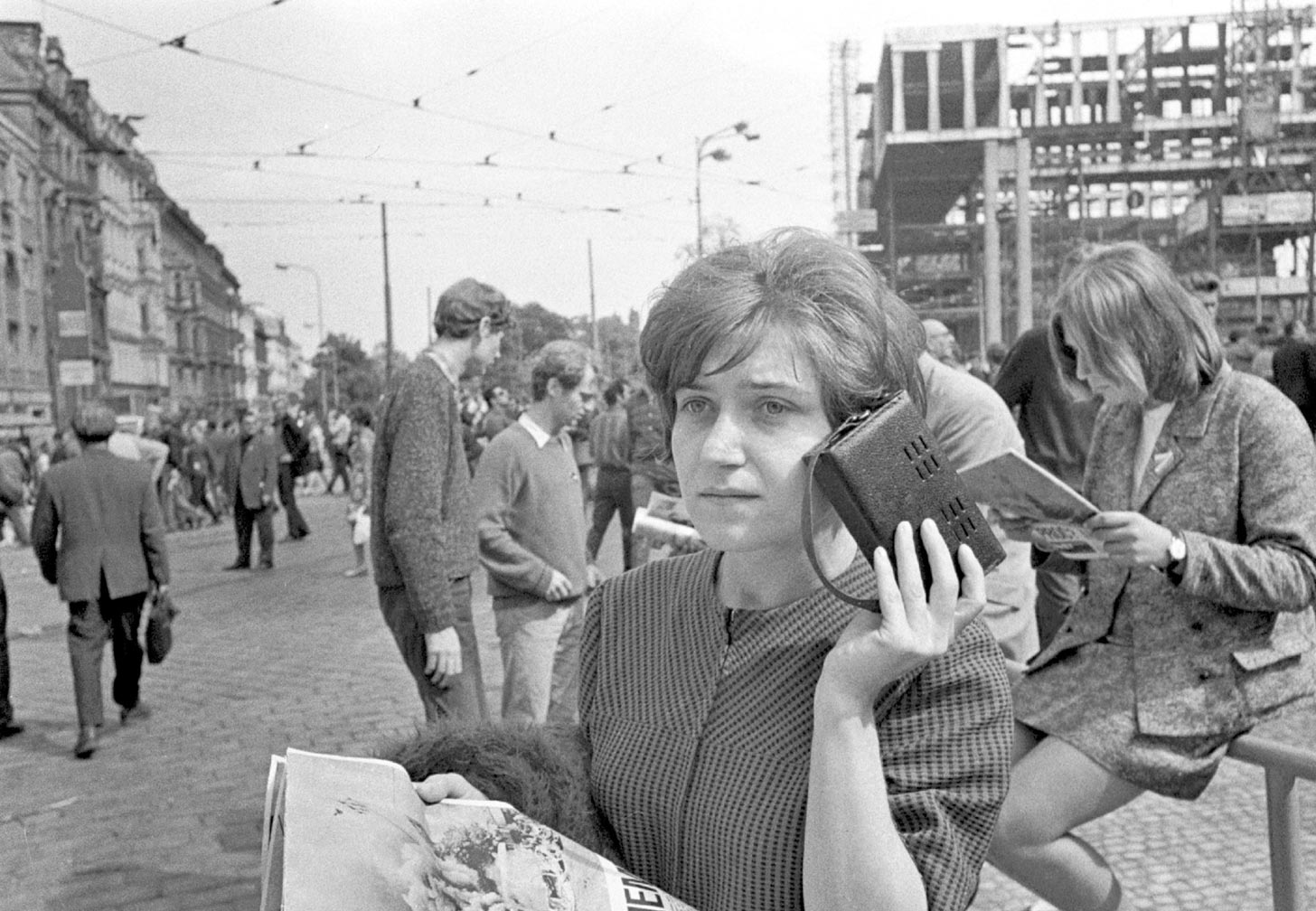

A woman on Prague's Wenceslas Square listens for news amid the invasion and clings to a local paper whose headline asks "Why?" in Czech and Russian. CTK

But as censorship was lifted, Czechoslovak media published explosive stories alleging corruption, murder, and other official wrongdoing. With newfound freedom to speak, Czechs and Slovaks began calling for fundamental political change.

From the Kremlin, Brezhnev and others watched with alarm as the Prague Spring began to melt Czechoslovakia's rigid state apparatus. The risk of democratic contagion became clear when students in Warsaw took to the streets and chanted their support for Czechoslovakia.

A Soviet tank aims its barrel squarely at the Matthias Gate of Prague Castle. CTK

Early on August 21, 1968, around 250,000 soldiers, 2,000 tanks, and hundreds of aircraft from the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland rumbled into Czechoslovakia. Just 29 years after the nightmare of the Nazi invasion, Czechs and Slovaks once again awoke to foreign troops on their soil.

Warsaw Pact troops stand guard outside Communist Party headquarters in downtown Prague on the first day of the invasion. CTK

Within hours, First Secretary Dubcek had been seized from his Prague offices (pictured in background) and flown to Moscow for interrogation.

Locals confront Soviet tanks and troops on Wenceslas Square in Prague. CTK

Bewildered Czechs and Slovaks erupted to challenge the invading soldiers -- many of whom were as uninformed as the locals -- on the streets.

Warsaw Pact troops fire into the air as they patrol Prague, sending locals scurrying for cover. Tiedemann/ullstein bild via Getty Images

The invading troops faced a population united in outrage, while their masters in the Kremlin heard near-universal condemnation from the outside world.

CTK

Although Czechoslovak troops remained on their bases, residents in some cases erected barricades, swapped street signs, or even attacked the invading armies with Molotov cocktails. But they were overmatched, and Czechoslovaks’ best hope seemed to lie in the mounting chorus of condemnation from the outside world.

Locals made a stand outside state radio's broadcast center in Prague, erecting obstacles and attacking tanks. Libor Hajsky (Reuters)

The most famous street battle was fought outside Czechoslovak Radio headquarters in the capital. Fifteen people died in the clash as crowds tried to prevent troops from taking control of the broadcaster.

A man waves a blood-spattered Czechoslovak flag as an armored vehicle carries Soviet troops through Prague. AFP

Some 137 civilians were killed in the invasion, as Warsaw Pact troops stamped out independent media and set the stage for Soviet-led efforts to "normalize" the situation in Czechoslovakia.

A man surveys damage in Prague on August 31, 10 days after tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia. AFP

As Czechoslovaks cleared their streets of blood and wreckage, Brezhnev declared Soviet readiness to intervene militarily if any other communist nation veered from the party line. Or, as one writer described the so-called Brezhnev Doctrine, "Workers of the world, unite or I'll shoot."