April 14, 2019

Nine-year-old Naveed Iqbal frequently accompanies his grandfather to mosque in this valley surrounded by the soaring peaks of the Hindu Kush mountains. But he doesn’t go inside — not yet, at least.

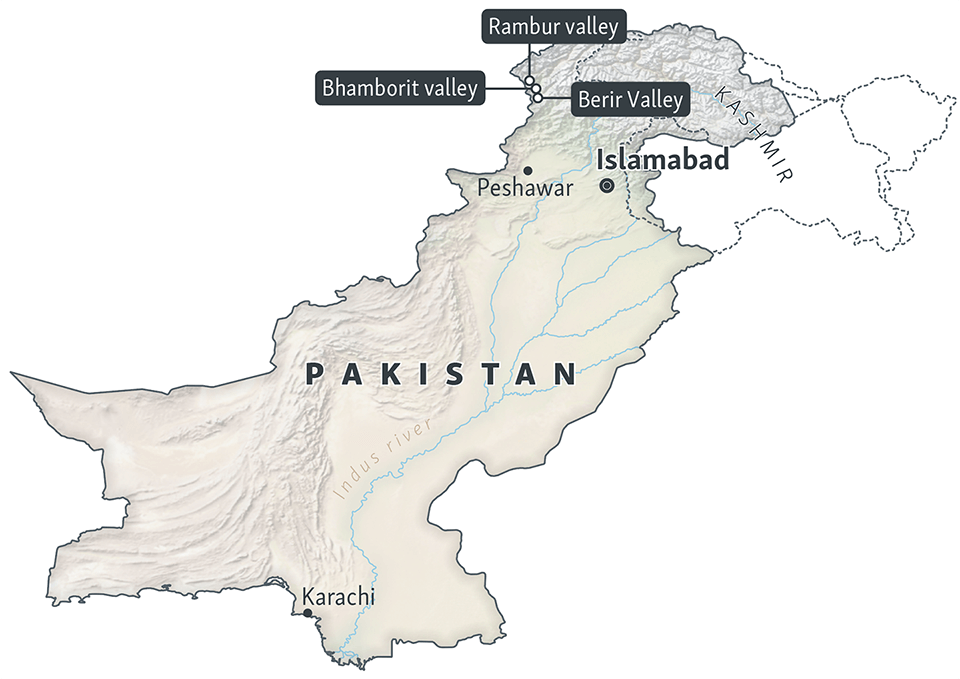

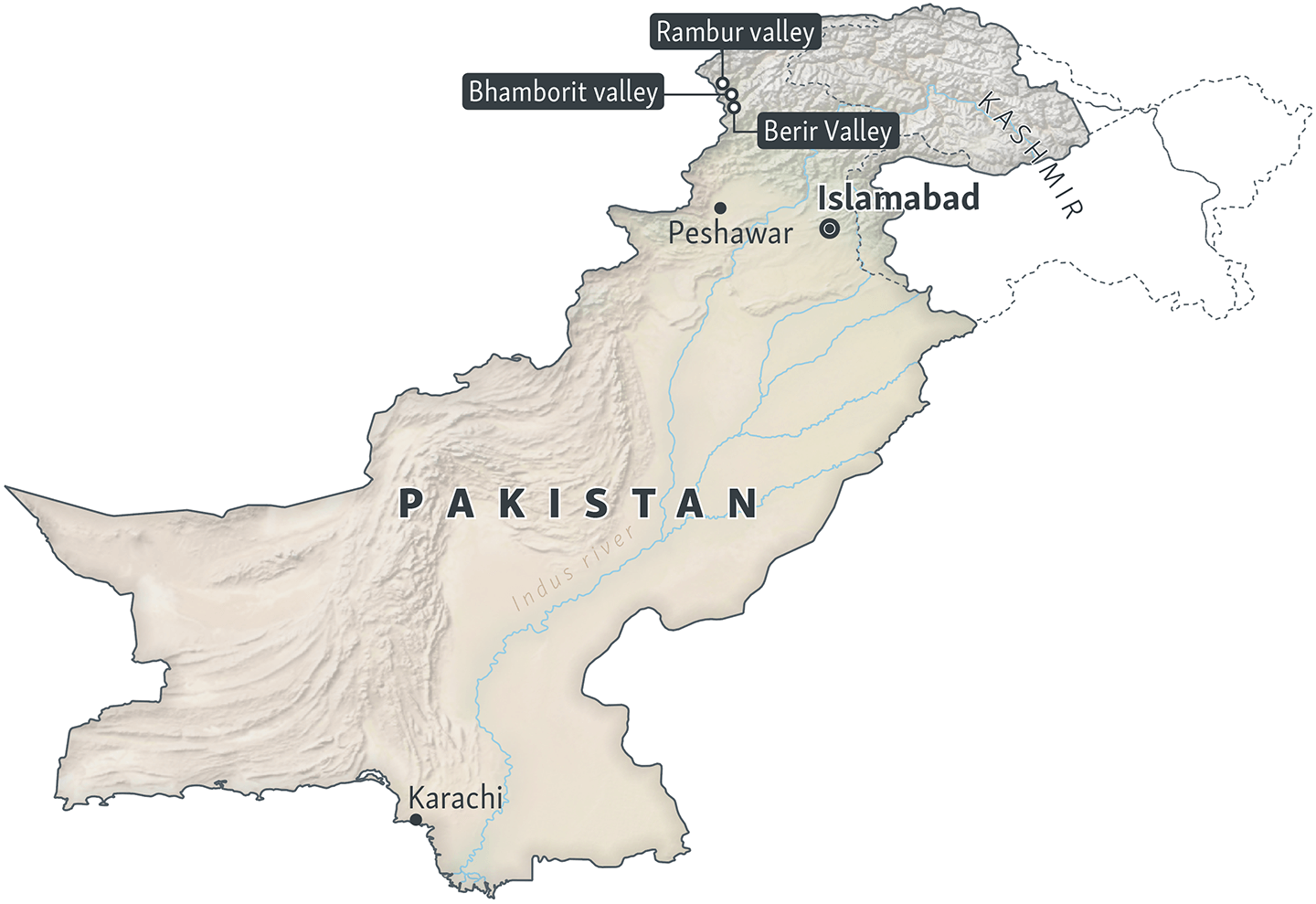

“When I go inside to offer my prayer, he waits outside on the mosque stairs until I come out,” his grandfather, Bilal Shah, told RFE/RL in an interview in this hillside village in Bhamborit, one of three idyllic valleys in the Chitral district of Pakistan’s northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province.

Naveed is a member of the Kalash, a pagan community known for their fair skin that has long inhabited this area near the border with Afghanistan. The Kalash people, many of whom believe they are the descendants of the armies of Alexander the Great, have held on to their religious beliefs and colorful rituals for centuries, even as a sea of Islam has encircled them.

But the unique traditions of the Kalash are coming under mounting cultural pressure as the pace of conversions to Islam accelerates within Pakistan’s smallest ethnoreligious community. The Kalash population currently numbers between 3,000-4,000, and locals estimate that some 300 of their members have converted to Islam over the past three years, The Washington Post reported in November. Some local reports, however, have said the figure is not that high.

Kalash children are not taught about their own culture, religion, or history in schools, where most of the teachers are Muslims. Calls to prayer now ring out five times a day from 18 mosques across the valley, the result of a recent boom in the construction of Muslim houses of worship. The swelling influence of Islam in the area has alarmed many in the Kalash community who worry that their traditional way of life is slipping away before their eyes.

And it is stoking tensions within families as well. Naveed, the nine-year-old who accompanies his grandfather Bilal Shah to mosque, is the son of Iqbal Shah, 33, who remains committed to carrying on the traditions of his Kalash ancestors. Bilal wants his grandson to grow up as a Muslim.

“He loves me. He stays most of the time with me rather than with his father,” said Bilal, a Kalash who converted to Islam 20 years ago.

Iqbal confronts Bilal whenever the grandfather raises the issue of the boy’s potential conversion.

“He is my son. I have the right to decide his future, or he himself has the right,” Iqbal said while sitting around a cast-iron wood oven in the guestroom of the family’s single-story house.

Asked by this reporter whose side Naveed takes in the matter, Iqbal translated the question for his son. Dressed in his school uniform, Naveed gave a shy smile as he raised his index finger and pointed it toward his grandfather.

‘Foundation For Conversion’

Tense relations between the Kalash and their Muslim neighbors are not new. The Kalash previously inhabited what is now the Nuristan Province in Afghanistan, just on the other side of the border with Pakistan. The area where they lived was at times called Kafiristan, or “Land of the Infidels” — a reference to their paganism. But in the late 19th century, the ruler of Afghanistan, Abdur Rahman Khan, launched a violent campaign against the Kalash to convert its members to Islam by force. Known as the “Iron Amir,” he proceeded to name the area Nuristan, or the “Land of Celestial Light.”

Many Kalash took refuge in the remote valleys of Bhamborit, Berir, and Rambur, in what is now Pakistan, where they continue to safeguard their religion and ethnic identity to this day. The local Muslims previously referred to the “infidels” of Nuristan as “red Kafirs,” who feature in the Ruyard Kipling story The Man Who Would Be King. Those who found shelter in the three valleys, meanwhile, were called “black Kafirs.” The moniker, which the Kalash abhor, is likely rooted in the black dresses that were worn by the women of the community. The word “Kalash” means “people wearing black clothes.”

The origins of the Kalash remain shrouded in mystery. Many Kalash believe their ancestors came to the area from a distant place known as Tsiyam, which Kalash priests and bards invoke in songs about their ancestors during colorful and exuberant festivals. Tsiyam is thought to be an area in southeast Asia, though no one knows precisely where — or what — it was.

Others in the community trace their ancestry to Alexander the Great’s armies that invaded this region in the 4th century B.C. A study by a team of geneticists published in 2014 found that the Kalash had portions of DNA from an ancient European population, suggesting a possible link to Alexander’s armies, The New York Times reported.

While recounting epics about their ancestors during festivals, Kalash elders speak of a man they believe was a general of Alexander’s, called Shalakash, who settled in the region. Historians believe the name refers to Seleucus Nicator, who indeed served as a general under Alexander and ruled over this region after the Greek armies left.

A genetic link between the ancient Greeks and the modern-day Kalash remains disputed. Some Pakistani anthropologists say they have found evidence of a Kalash presence in the area well before the arrival of Greek armies in the region. And a 2015 study by Pakistani, Italian, and British scientists found that the Kalash share genetic likeness to Paleolithic Siberian hunter-gatherers “and might represent an extremely drifted ancient northern Eurasian population that also contributed to European and Near Eastern ancestry.”

“The genetically isolated Kalash might be seen as descendants of the earliest migrants that took a route into Afghanistan and Pakistan and are most likely present-day genetically drifted representatives of these ancient northern Eurasians,” the researchers said, adding that their study did not find support of a Kalash link to Alexander’s soldiers.

The names of the Kalash gods and goddesses, however, resemble those of the Greeks. And many words in their language resemble Greek as well. Their language, called Kalash or Kalasha, is a Dardic tongue that is in a subgroup of Indo-Aryan languages spoken in the area. It has no script and the traditional Kalash stories are passed down orally from generation to generation.

There is no separate curriculum for Kalash children in local schools that would teach them the language and traditions of their people. But they are taught Islamic theology and Koranic scripture alongside Muslim students.

“This lays the foundation for the conversion of the Kalash at this stage,” a teacher, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told RFE/RL during a visit to a school in Karakal, which has a population of around 350.

Wazir Zada, who represents the Kalash community in the provincial legislature, said he intends to raise the issue in the assembly. "I hope we will be able to introduce the teaching of Kalash culture and religion in schools," Zada, 35, told RFE/RL.

‘Abandoning’ A Lifestyle

Bilal Shah, who hopes his grandson Naveed becomes a Muslim, says he converted 20 years ago after attending a gathering of Tablighi, the missionaries who travel around the country preaching a conservative, apolitical, and pacifist version of Islam. “I was impressed by the presence of religious scholars and, thanks be to God, entered into the fold of Islam,” he told RFE/RL.

As he spoke, Bilal guided this reporter through a cemetery just behind his house to the grave of his mother, who died as a Kalash. Those who convert to Islam here opt to be buried in Muslim cemeteries.

Pakistani authorities have now banned Tablighi from entering the valley following a clash between members of the Kalash and Muslim communities over the conversion of a Kalash girl to Islam in 2016. But the Muslim missionary work continues within the Kalash community and families like the Shahs: With their relatively liberal and tolerant approach toward religion, they do not expel or otherwise pressure a family member who converts to Islam or adopts another faith.

“Once someone converts in a family or neighborhood, he or she becomes a local source of inspiration and influences the others’ beliefs to attract them to Islam,” Iqbal Shah, the son of Bilal and father of Naveed, told RFE/RL.

Iqbal’s parents, sister, and one brother have already adopted Islam, while his other brother continues to adhere to the traditions of the Kalash. This coexistence has a negligible impact on the routines of the family’s daily life, though occasionally the choice of food or drink can be a source of annoyance. Bilal, for example, does not approve when Iqbal partakes of the locally produced wine — another cultural tradition that the Kalash share with the ancient Greeks.

Many locals say that educated young women here more frequently convert to Islam and marry outside the Kalash community than their less-educated peers. Some elope with Muslim men from cities, and parents and relatives say the temptations of modern life and technology play a role in these marital decisions — and are gradually damaging their culture.

The Kalash subsist largely on farming, growing crops such as maize, and raising livestock for milk, cheese, and meat. Women toil in the fields and collect wood, while others work as masons and artisans. Otherwise the employment opportunities in the area are sparse beyond working as teachers, security or border guards, or at local guest houses that operate mainly during the festivals.

“When young people get an education, they seek jobs in cities far away from the valley and don’t return here for months and even years,” Shahzada Khan, a 55-year-old hotelier from Krakal, told RFE/RL. “Their detachment keeps them away from their culture and religion, and they totally abandon this lifestyle in due time.”

Shaira, a 27-year-old Krakal resident, is one of the educated young women here who says she wants to remain within the Kalash community and uphold its centuries-old traditions. Shaira, who holds a master’s degree in international relations from the University of Peshawar, says her older sister eloped with a young Muslim man from the southeastern Sindh Province a year ago. The family has only spoken with the sister periodically. The young man’s family strictly follows Islam and does not want her interacting with “infidels,” Shaira said, adding that she herself wants to marry a Kalash man.

“My culture gives me the freedom to choose my life partner, and if I am not happy with him, I have the right to choose another man. No other religion or culture gives me that choice.”

The Kalash are distinct from the rest of Pakistan not only in terms of their religion, colorful dresses, and comparatively fair skin, but also with their liberal approach to marriage. A woman is free to marry for love, and if she sours on her husband, she is allowed to divorce him and even elope with another. The only condition is that the new husband must pay a dowry to the previous one that is double the original.

In most of rural Pakistan, Muslim women largely remain behind the four walls of their homes, cover their faces in streets and markets, and are not allowed to speak to men other than their close family members. Kalash women freely interact with local and visiting men.

In rural areas, young Muslim couples who elope are sometimes targeted in so-called “honor killings” — a practice putatively aimed at preserving a family’s honor that Pakistani lawmakers have tried to stem by introducing harsher punishments for these crimes.

“My culture gives me the freedom to choose my life partner, and if I am not happy with him, I have the right to choose another man. No other religion or culture gives me that choice,” Shaira, who proudly wears traditional Kalash robes and dresses, told RFE/RL.

While the Kalash are highly tolerant of other religions, the community’s elders have strictly prohibited the reentry into their own by those who have converted to Islam. That move was driven in part to protect the converts from potential reprisals for leaving Islam. Unlike blasphemy, apostasy is not punishable by death under Pakistani law, but a 2013 Pew Research Center survey found that 62 percent of Muslims in Pakistan are in favor of capital punishment for those who leave Islam

The crime rate is almost zero in the area, where the locals can enter one another’s homes without a knock. But in 2016, violent clashes — which prompted the ban on Tablighi in the area — erupted between Muslims and Kalash in the Bhamborit Valley after rumors that a 14-year-old girl had backtracked on her conversion to Islam and returned to the Kalash religion.

The girl, named Rina, later claimed at a news conference alongside Kalash and Muslim leaders that the violence was the result of confusion over her choice of garb — and that she had not given up Islam.

“I wore the robe after a Muslim relative told me I was still a minor and could dress up in our traditional attire. She told me I could revert to Muslim shalwar-kameez dress once I had grown up, so I wore the dress,” she was quoted by the BBC as saying.

Attempts to locate Rina were unsuccessful, and locals declined to give details about her whereabouts.

A House Divided

Kalash men and women mingle at the flurry of festivals they stage throughout the year, where the feasts are lavish and the wine flows. Singing and dancing are at the heart of these festivals celebrating harvests, flowers, each of the four seasons, and the weather. At each event, the Kalash pay tribute to their gods and goddesses — including by sacrificing goats — as music from flutes and drums fills the air. The local Kalash museum features some other types of traditional instruments, but almost no one knows how to play them.

The mood is even celebratory when someone dies. The Kalash take the body to the temple, known as Jastkan, and invite community members from all three valleys to dance and sing around the recently deceased for two days. The burial is marked with a large feast for which dozens of goats are sacrificed to feed the guests, who use song to praise the dead.

The final annual festival each year, a week-long celebration, known as Chomas in the mountainous world of the Kalash, begins on December 16. Like other festivals throughout the year, it features song and dance and animal sacrifice. During Chomas, the Kalash ask their deities to protect them from a cold and snowy winter.

One unique feature of this winter festival is that the Kalash and Muslims are segregated for a three-day period during the festivities. The Kalash living in the predominantly Muslim part of the village leave their homes to join their fellow pagans for the festivities, while the Muslims in the Kalash section voluntarily leave their homes as well.

Iqbal Shah and his family live in the home of his father, Bilal, which stands in the Muslim section of Krakal some 50 meters from the mosque that Bilal takes his adoring grandson Naveed to. On the first day of the most recent winter festivities, Iqbal prepared to depart the home with his wife and family.

“This is now becoming pretty common in these valleys, because each family has [converted] Muslim members,” Iqbal said.

Just before Iqbal left the home with his wife and four children, Bilal kissed Naveed on both cheeks and bid farewell to half of his family.

“This was not happening a few decades ago,” Bilal said.

Bilal added that he prays that Allah will help other Kalash convert to Islam, and that such sendoffs “will not happen again.”

“I invite them to Islam,” Bilal said. “What else can I do? I can invite them and only Allah can guide them to the right path.”

- Edited by Carl Schreck