Putin's Visitors: Bribes, Lollipops, And A Big 'Meh' From Liz Cheney Records detailing Vladimir Putin's time as a controversial St. Petersburg committee head in the 1990s are sparse. RFE/RL digs into a handful that reporters were able to obtain -- and reveals the stories behind their scant contents.

ST. PETERSBURG -- In a residential neighborhood on the outskirts of St. Petersburg there is a nondescript beige-and-brown building that looks a bit like a neighborhood health clinic. It is the state archive building, where thousands of documents from the city administration are stored -- minutes of meetings, official orders, staffing records, interagency correspondence, and the like. But there is one remarkable gap in the archive’s catalog. There are no documents about the work of the city’s External Affairs Committee (KVS) from the period in the early 1990s when it was headed by a former KGB operative named Vladimir Putin.

Around four dozen records related to Putin's tenure there have been preserved thanks to Marina Salye, a city lawmaker who alleged corruption in deals he signed off on.

But here at the state archive, the only way to learn anything about the work of this important committee is by looking through its official monthly bulletins -- not all of which are preserved -- or a couple of its annual reports. If any documents signed by Putin or his now-famous subordinates Igor Sechin, Dmitry Medvedev, and Aleksei Miller still exist, they are held in some other archive.

This report is the fourth installment of an investigative project examining the scandals and scams that swirled around Vladimir Putin and his associates during his tenure as a St. Petersburg city official in the 1990s.

But even the officially available documents give intriguing glimpses into the daily working life of Putin's team in the Soviet Union's final months and the first couple years after its collapse. Current Time and RFE/RL's Russian Service have scanned the available monthly bulletins and the committee’s annual reports for 1991, 1992, and 1993, and are publishing them for the first time. All the documents gathered for this investigation into Putin's first steps in politics and government can be seen here.

- Report on foreign relations for 1991 of the executive committee of the Leningrad city council

- Report on the work of the External Relations Committee, June 1991-May 1992

- St. Petersburg External Relations Committee informational bulletins for 1992, Nos. 1-16

- St. Petersburg External Relations Committee informational bulletins for 1993, Nos. 17-43

Under the heading of Meetings Of The Week in the committee’s monthly bulletins, some interesting topics crop up. Many of the meetings are talks with potential foreign investors, as might be expected. But there are some more captivating entries that tie the committee to entire stories, including some featuring the remarkable corruption of St. Petersburg officials that foreign partners often complained about.

There's also a record of a long-forgotten meeting between Putin and a twentysomething U.S. aid official who is now one of the most prominent members of the U.S. Congress: Liz Cheney.

Surreal Suckers

The KVS documents uncovered by RFE/RL and Current Time shed light on various connections between Putin's committee and businessmen from Spain's Catalonia region.

Example: In the KVS bulletin from November 1992, under the section Orders Of The Mayor Of St. Petersburg, there’s mention of a project to build a wholesale-retail market "like Mercarbana [sic]" -- an apparent reference to Barcelona's Mercabarna market.

According to a report in the Spanish newspaper El Pais, St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak came up with the idea after a trip to Barcelona with Putin in 1992. Putin’s secretary, Sechin, who was also part of the 1992 Barcelona delegation, was assigned to the working group on designing and building the market, although nothing further came of this idea.

Manuel De Forn, a planning official from Barcelona, came to St. Petersburg to discuss the idea with Putin. He recalled learning that while it would be possible to build the market, there were no goods to be traded there. The city simply did not have such quantities of food and other goods.

De Forn also mentions the huge problem of corruption.

"Putin didn't directly ask us for money, but other people told us what we needed to know about the bribes," De Forn said, according to El Pais. Ignacio Ferrero -- owner of the Spanish firm Nutrexpa, which in turn owns the brand Cola Cao that Russians remember from its ubiquitous advertising -- made similar claims to Spanish journalists.

Other Spanish businessmen from the era also complained about the pervasive corruption in Russia. The head of the company that produces the sparkling wine Freixenet, Josep Ferrer, described the "red mafia," a network of firms organized by former members of the Soviet KGB that one had to deal with for "protection" and the criminal gangs connected with those firms.

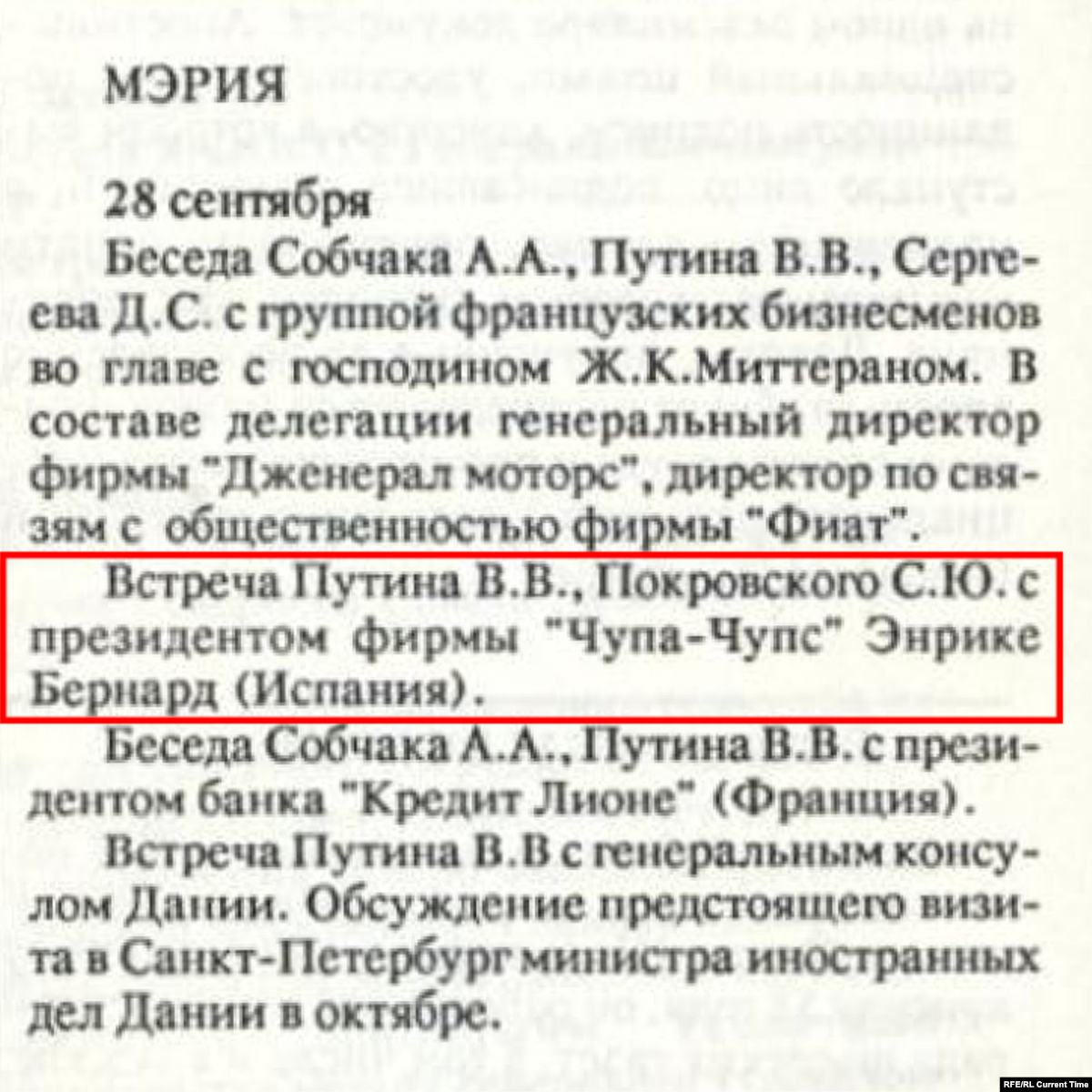

Another Catalonia-related meeting took place on September 28, 1992, according to the committee bulletins. Putin, together with the chairman of the city's Foodstuffs Committee, Sergei Pokrovsky, held a meeting that brought him just one degree of separation away from the renowned surrealist painter Salvador Dali.

On that day, he sat down with Catalan businessman Enric Bernat, president of the confectionary firm Chupa Chups -- though his surname is listed in the bulletin as "Bernard," in the Castilian style. Bernat was the man who invented the idea of a caramel candy on a stick to help keep sticky candy off kids' hands and clothes.

When he wanted to bring Chupa Chups to the global market in the late 1960s, Bernat turned to his longtime friend, Dali. According to legend, in a few hours Dali created a logo for the candy that is still in use, virtually unchanged, to this day.

The meeting with Putin may have been successful: Chupa Chups did build a candy factory in St. Petersburg. The company also purchased stakes in the Russian candy maker Azart and the Garantia insurance company. Chupa Chups is very well-known in Russia, where it has continued to operate after the invasion of Ukraine this February.

Some other efforts by Catalans to enter the Russian market were not successful. And the main reason why -- according to their own recollections -- was the massive corruption of city officials. This lack of success came despite the fact that a leading Catalan businessman, Lluis Prenafeta, once helped save the life of Russia's first president, Boris Yeltsin.

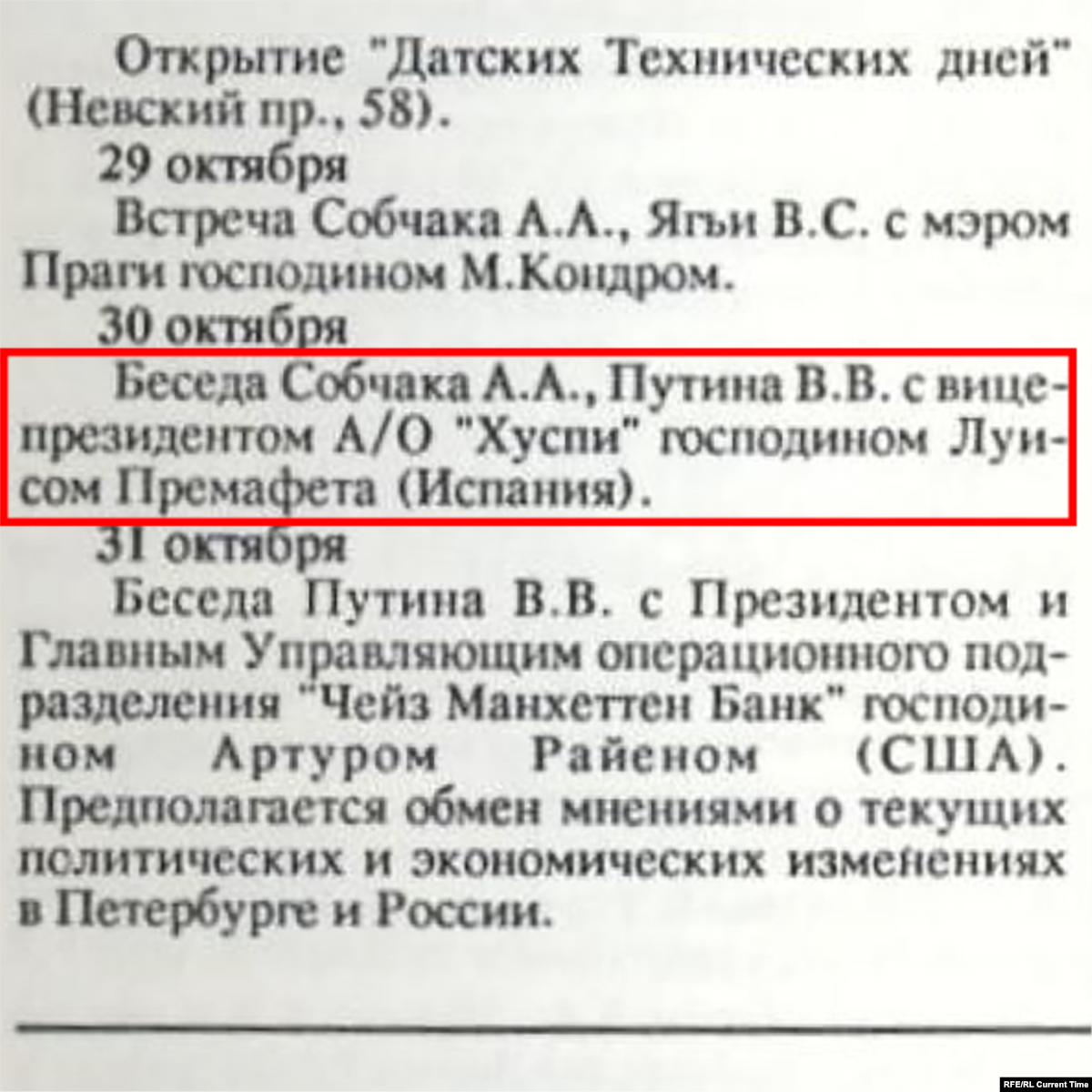

On October 30, 1992, Sobchak and Putin -- according to a couple laconic lines in the KVS bulletin -- met with “Mr. Lluis Premafeta [sic],” vice president of a company called Juspi that had been created specifically to invest in Russia. Equal stakes in Juspi were held by Bernat and Prenafeta.

Juspi was supposed to import foodstuffs to Russia and create a network of gas stations. Prenafeta at that time was the CEO of the Spanish state oil company Petrocat. A cooperation agreement was signed when Sobchak -- along with Putin and Sechin -- travelled to Barcelona in February 1992 at the invitation of that city's mayor.

It was exactly one month before Marina Salye, the St. Petersburg municipal lawmaker, handed a top Yeltsin aide, Yury Boldyrev, the findings of her commission about alleged corruption in the city's program to export commodities in exchange for badly needed food imports.

Marina Salye

The St. Petersburg Lawmaker Who Became Putin’s First Accuser

At the time, Prenafeta was one of the most influential people in Catalonia, involved in both business and politics. He was the right-hand man of Jordi Pujol, the head of the autonomous Catalan government. In that capacity, he oversaw the creation of an independent Catalan broadcasting company, published a newspaper, and traveled the world as the region's envoy. Spanish journalists wrote that Prenafeta arranged meetings for Putin with prostitutes, reports that Prenafeta denied.

Prenafeta's name began appearing in the Russian press in 1992. According to reports, the October meeting with Putin was far from the only one he held in Russia. Kommersant wrote that Prenafeta also met with acting Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar and several Russian government ministers as part of an effort to negotiate the exchange of Russian oil for Spanish technology and foodstuffs.

Operation Yeltsin

The first mention of Prenafeta in connection with Russia, however, dates back to 1990 and contains the seeds of a real thriller. Viktor Yaroshenko, former minister of foreign economic relations in the government of Soviet Prime Minister Ivan Silayev, recalled for RFE/RL how he traveled with Yeltsin to Spain that spring for an international conference in Cordoba. That trip nearly ended tragically for Yeltsin, Yaroshenko said.

After the Cordoba conference, Yeltsin was scheduled to take an air taxi to Barcelona, where he had been invited by Catalan leader Pujol. But in midflight, the light aircraft developed a problem with its generator and its backup electrical system. The pilots managed to make an emergency landing at a remote mountain airfield, but it was a hard landing. Yaroshenko said the plane "nearly crashed" into the runway, and the landing was hardest for those -- like Yeltsin -- in the very back of the plane.

Yaroshenko related how the delegation made it to Barcelona in another plane but by the time they arrived, Yeltsin was experiencing sharp pain in his lower back and was nearly paralyzed. During the landing, it turned out, Yeltsin had suffered a herniated disc and a pinched nerve.

Yeltsin underwent emergency surgery in Barcelona. Although the press reported widely about the event, journalists did not report that it was Prenafeta who arranged the emergency operation for the Soviet politician about a year before he was elected president of Russia.

Spanish journalist Salvador Sostres revealed this little-known fact in 2017. He wrote that Yeltsin expressed his gratitude by inviting Prenafeta to Moscow, where the two met in the Kremlin. Prenafeta arrived in Russia as Bernat's representative and tried to negotiate the purchase of beet fields to produce sugar.

A Crude Fabrication

There is one more episode connecting Prenafeta and Russia that occurred between the Yeltsin incident and the October 1992 meeting with Putin. He arrived in Moscow a second time with a proposal to purchase cheap Russian oil in exchange for food.

According to a 2008 account by Spanish journalist Antonio Fernandez in the newspaper El Confidencial, Prenafeta "paid a fortune" to get permission from the Russian Energy Ministry to export Russian oil to Spain. But when the permission arrived by fax in his office in Barcelona, Prenafeta rushed to Moscow, only to be told that the fax in his hand was a crude fabrication.

In St. Petersburg, Fernandez wrote, Prenafeta encountered other problems despite his meeting with Putin. In addition to discussing the sale of food and tobacco products, Prenafeta brought along Arturo Suque, the owner of three Catalan casinos.

Suque and Prenafeta tried to sell the mayor's office on the idea of creating a regional lottery in St. Petersburg, but they again found themselves duped. According to a 1994 report in El Pais, they were given fake documents with permission to create the lottery and were told that after publication of the document in the city government's official newspaper they would have to pay 200 million pesetas (around $3 million at the time) to finalize the deal.

A short time later, however, Prenafeta learned that the lottery concession had been awarded to American billionaire Ted Turner, the founder of CNN.

"They kicked us from one office to another, wasting our time and our nerves," Prenafeta said in an interview with the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia about his St. Petersburg trip. Javiar Bernat, Enric Bernat’s son and heir, recalled that Juspi encountered unbelievable corruption among Russian officials, each one of which he said had to be given a bribe of at least 20,000 pesetas (the equivalent of $320 today).

In order to implement any agreement in Russia, Javiar Bernat said, one had to sign contracts with intermediary firms "recommended" by officials and hire Russian lawyers, the payments for whom mostly ended up in the pockets of bureaucrats.

Give And Take

In Spain, Prenafeta has been dogged by corruption charges himself.

In October 2009, he and several colleagues were arrested as part of a major corruption investigation by Judge Baltasar Garzon. The previous year, Garzon had investigated the Russian mafia in Spain and had even planned to fly to Moscow to question Kremlin-connected businessman Oleg Deripaska. As part of that investigation, which focused on the St. Petersburg-based Malyshev crime group, Spanish authorities searched the Spanish villa of Vladislav Reznik, a parliament deputy from the ruling United Russia party.

In August 2009, during questioning by Garzon, a career criminal named Luis Rodriguez Pueyo testified that in April 2008, on Reznik’s instruction, he had tried to kidnap the son of Spanish billionaire Francisco Hernando. Pueyo said the order was given because Hernando refused to repay a $30 million debt to Gennady Petrov, the notorious boss of Russia’s Tambov crime group, which also operated in St. Petersburg.

In December 2009, Prenafeta was released from custody on a $1 million bond. In 2017, he cut a deal with prosecutors and agreed to pay a fine of almost 25 million euros for concealing income from tax authorities, according to El Pais.

After that, Prenafeta's business and political career went into steady decline, and he is now a retiree who has written several autobiographical books. Several efforts to contact him for this report were unsuccessful.

In his memoirs, Prenafeta speaks about his adventures in Russia in the early 1990s, summing them up by saying they resulted in "complete catastrophe."

Nonetheless, contemporary Catalan politicians have warm relations with Putin's Russia, which in 2019 led to accusations that the Russian military intelligence service known as the GRU was behind a Catalan independence referendum that was denounced as illegal by the Spanish authorities.

14 Hours With A Grenade

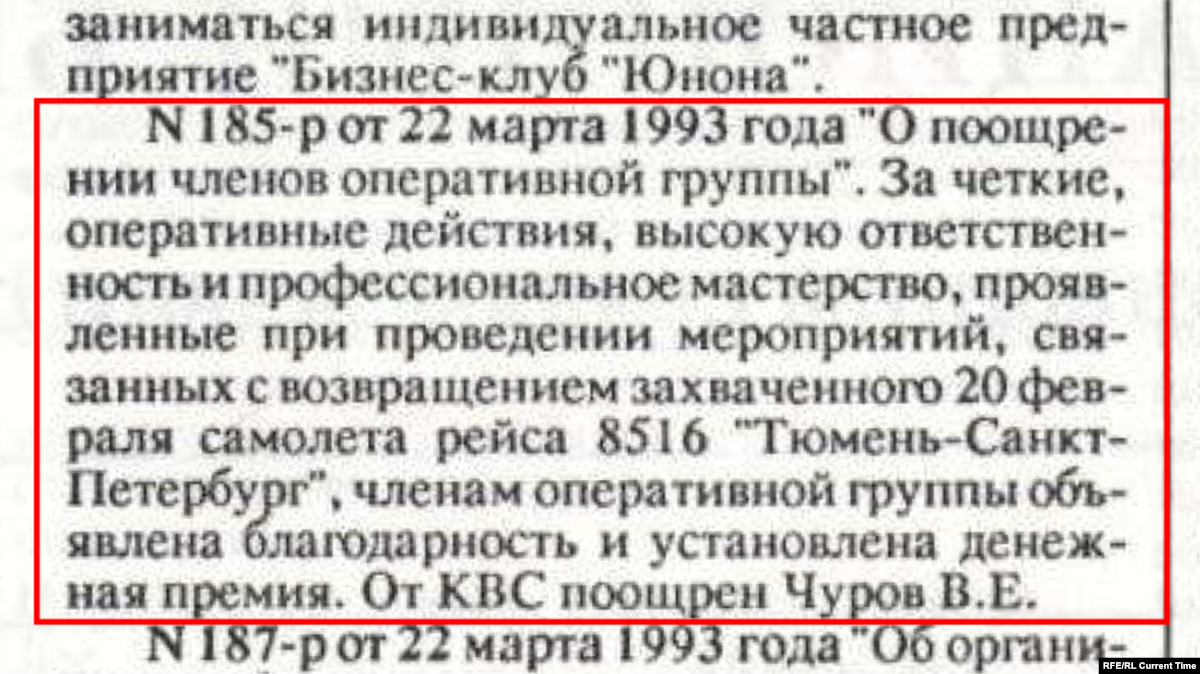

The KVS bulletin from 1993 contains a small passing reference to Vladimir Churov, who would go on to serve as chairman of the Central Election Commission under President Putin, overseeing several elections rife with allegations of fraud, and who at that time was a KVS senior specialist.

To Touch Putin's Door Handle

The Scandal-Rife Committee That Launched Putin’s Political Career

In the notice, Churov is thanked for his "professionalism" in helping return to Russia a commercial airliner that had been hijacked to Sweden while flying from Tyumen to St. Petersburg. It remains unknown exactly what role Churov played in this process. The KVS may have used its contacts with Sweden to help the Russian air carrier to secure the release of the plane.

But this tiny notice in the bulletin connects Putin's committee with the remarkable story of the hijacker -- the vengeful cat lover Tamerlan Musayev.

In 1993, a street busker from Baku named Tamerlan Musayev, together with his wife and 7-month-old daughter, hijacked the flight from Tyumen to St. Petersburg. Musayev was trying to avoid being conscripted into the military as the conflict in the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan was unfolding.

Musayev secured two hand grenades from a friend who had deserted from the military and traveled with his family to Tyumen. He regularly traveled there to sell goods he bought in Turkey and was very familiar with the disorder in the Tyumen airport. He even claimed he knew a pilot on the Tyumen-St. Petersburg flight who would allow passengers on board for free. He said he paid the head of a baggage crew 30,000 rubles (about $5 at the time) to bring the bag with the hand grenades to the plane's boarding stairs.

During the flight, Musayev pulled the pin of one grenade and sent it, together with a note, to the cockpit. The hijacker demanded to be flown to the United States, but the pilots explained to him that the Tu-134 passenger jet would need to refuel. They initially mentioned the idea of going to Finland, and then the crew convinced Musayev they could go to Sweden after refueling in Estonia.

In Tallinn, Musayev released 15 mostly elderly passengers, although one of them reportedly snuck back onto the plane because he wanted "to go to Europe." The plane's flight crew was able to sneak another 15 passengers out through a baggage door.

In Stockholm, the Musayevs ran out of diapers for the baby. The authorities dangled the possibility of granting political asylum. So Musayev, who had purportedly been holding the live grenade in his hand for 14 hours, surrendered. Asked in later interviews whether the grenade was really live, Musayev answered evasively.

Musayev was arrested and placed in a cell that he later compared to a "sanatorium." The story was widely covered by Swedish media, and the family was briefly a sensation there. Musayev expected to serve a short sentence in Sweden and then be granted political asylum, particularly because Swedish law barred extradition to countries where the punishment for a crime was significantly harsher than the punishment for the same crime in Sweden.

But a Swedish judge decided that a hijacker could expect a five-year term in both Sweden and Russia, so he sent the Musayevs back to Russia. Musayev, through the media, begged the Swedish authorities at least to allow the baby to stay, but they refused.

In St. Petersburg, Musayev was sentenced to 12 years in prison, while his wife got six.

Musayev was released in 2002 after serving 9 1/2 years. And has spent the ensuing years pursuing a monomaniacal quest for "revenge" against Sweden, filing fake bomb threats in 2014, 2016, 2017, and 2020.

"Two goats -- me and Sweden -- have met on a bridge and both refuse to give way," he said in a 2020 interview with St. Petersburg’s Fontanka.ru website. "I understand that it is embarrassing for them that some worker from Russia is pressuring them. But I insist that Sweden cannot spit in the face of a Russian citizen. I want them to tremble at the sight of a Russian passport."

In the summer of 2021, Musayev was waiting in a Dutch migration center for deportation to Russia. He apparently had changed his opinion about Russia and told a local newspaper that he wanted to remain in a country where he could freely express his opinions about the Russian government.

"I want to publish articles critical of the government," he said. "In Russia, this is impossible. So it is dangerous for me to return. If I return, I will be arrested by the [Federal Security Service]. They'll put me in prison on fabricated charges."

On March 16, 2022, Musayev wrote that he was still in the Dutch migration center with his cat, Gusya. The Dutch authorities regularly deny his requests for asylum, he wrote, but he expressed confidence that "genuinely independent judges" would overturn their decisions.

'Left No Impression At All'

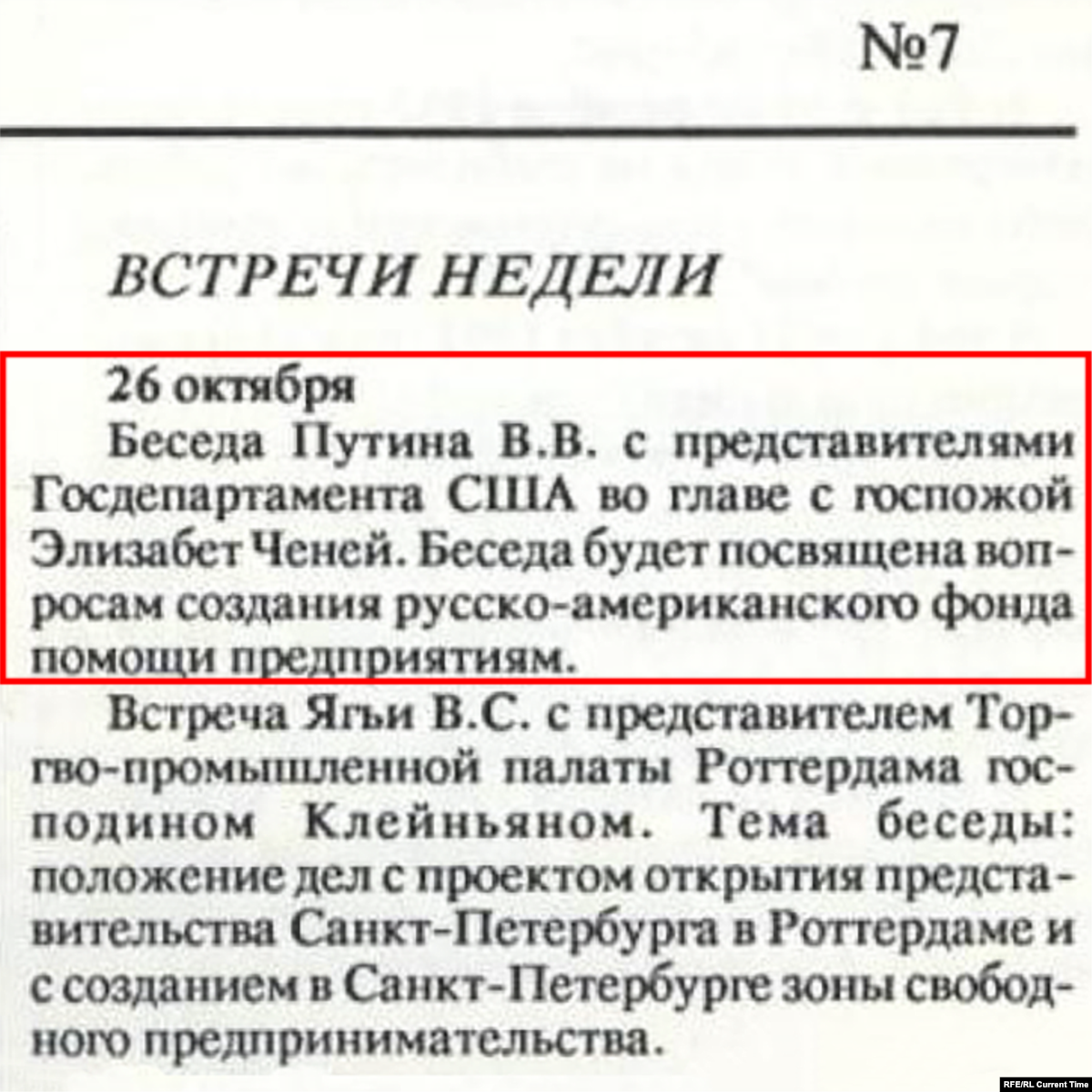

According to a small notice in the KVS bulletin, Putin met in October 1992 with a delegation from the U.S. State Department. The agenda for the meeting included discussion of the creation of foundation for the support of Russian business. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), an organization that Putin’s government barred from Russia 20 years later, participated in the project.

The bulletin reports that the U.S. delegation was headed by Elizabeth Cheney, then a 26-year-old USAID employee and the daughter of then-U.S. Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, who would go on to serve two terms as President George W. Bush’s vice president. Liz Cheney later became a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives who has been vilified by many in her party for her criticism of President Donald Trump.

Cheney's representatives told RFE/RL that her talks in Russia at that time -- which were held in several Russian cities -- were to discuss humanitarian-aid programs.

On April 12, 2022, Cheney, together with all the other members of the U.S. Congress, was placed under sanctions by Russia. Cheney, who has been harshly critical of the Russian government's authoritarianism, called her appearance on the sanctions list "a badge of honor."

Cheney told RFE/RL in an e-mailed statement what she remembered about her 1992 meetings in Russia:

"Vladimir Putin left no impression at all," she said. Instead, she recalled the colorful governor of the Nizhny Novgorod region, Boris Nemtsov, "who dedicated his life to fighting for freedom."

After Putin became president, Nemtsov was one of his most outspoken and popular critics. He was assassinated near the Kremlin in February 2015.

"For his dedication to this cause and because Putin was so threatened by him, Nemtsov was murdered by Putin's thugs," Cheney said. "Nemtsov's children and his country will long honor his memory. History will remember Vladimir Putin as an evil and insecure war criminal."

Robert Coalson contributed to this report.