To mark the 30th anniversary of the committee on which Russian President Vladimir Putin cut his political teeth, the city of St. Petersburg published a tribute book that included an anecdote about tour guides at the Smolny Institute, which housed the city's executive branch in the 1990s.

"During tours, they tell guests there is a superstition that if you touch the door handle of Vladimir Putin's office, you can expect career advancement," the book states.

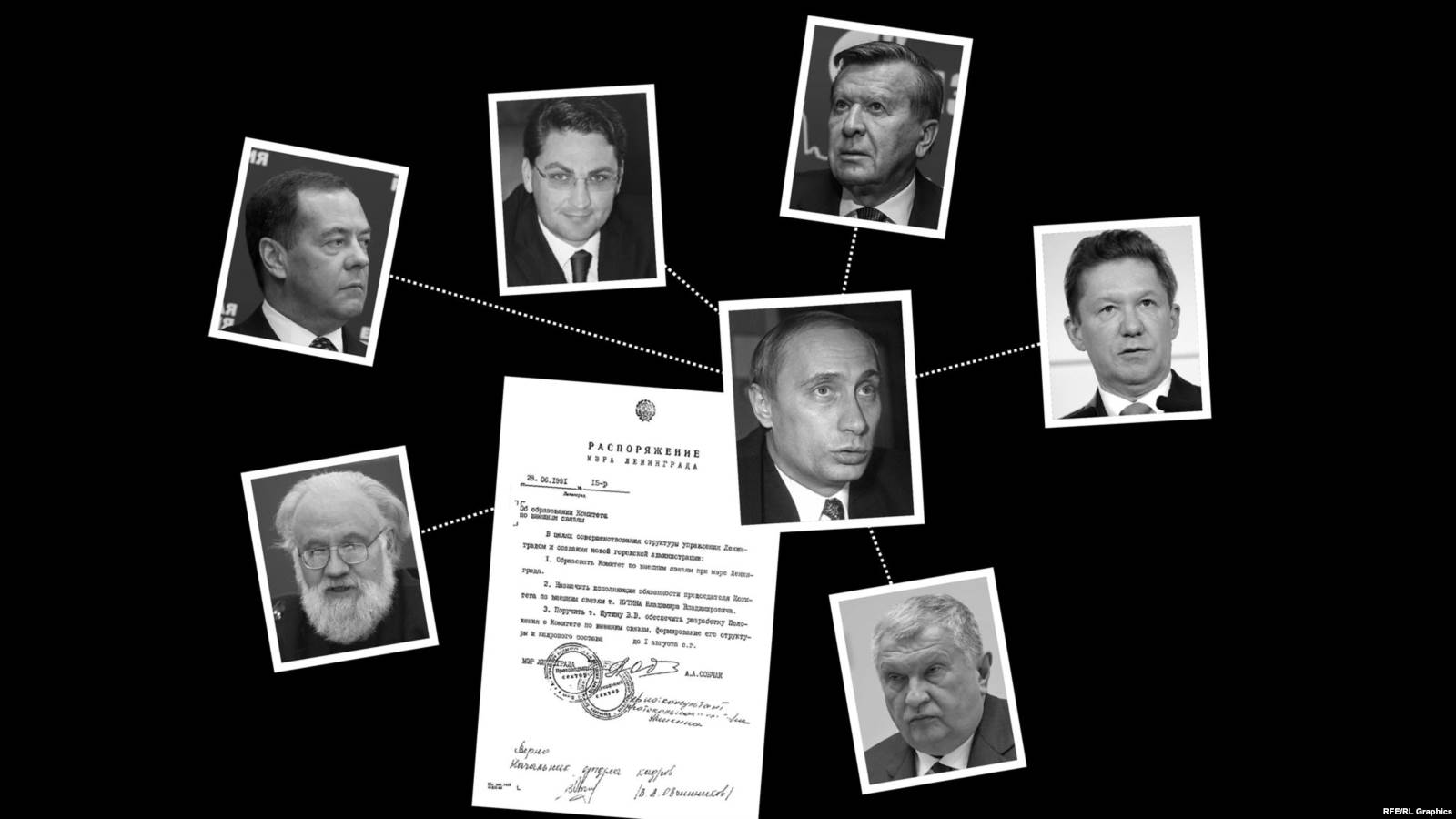

Putin took the reins as chairman of the St. Petersburg mayor's External Relations Committee (KVS) in June 1991 -- two months before a failed hard-line coup that hastened the Soviet collapse. It was the first major political job for the 39-year-old former KGB officer, and before a decade had elapsed, he had moved all the way up the ladder of power to the Russian presidency.

But exactly what was the KVS, and what did it do?

The same book tells the committee's origin story. It states that because the Russian Foreign Ministry was unable to immediately assume the authority and responsibilities of the Soviet Foreign Ministry, regional and municipal authorities were left to fend for themselves when it came to foreign economic relations.

“Under those circumstances, Leningrad/St. Petersburg, where such contacts were well developed, needed a rapid and radical restructuring of the foreign economic activity of the new administration headed by Anatoly Sobchak, who selected Vladimir Putin as head of the External Relations Committee and appointed him first deputy mayor," the book states.

Former committee member Vladimir Churov, who went on to serve as head of the Russian Central Election Commission from 2007 until 2016 and who was accused by Kremlin opponents of overseeing rigged elections, wrote that from the beginning, the committee worked "to create the conditions for cooperation with the West under free-market circumstances."

Committee members met with representatives of Western companies from Coca-Cola to leading French and German banks, negotiating investment projects in the city.

The most prominent and scandalous chapter in the history of the committee involved early agreements to export commodities like oil and rare-earth metals in exchange for badly needed food supplies. In many cases, the commodities were duly exported, but the food never arrived. In his memoirs, Putin blamed dishonest suppliers for the discrepancies, but deputies from the Leningrad city council suspected corruption.

In 1992, just months after Putin's committee started work, the council formed a special commission headed by one of its members, Marina Salye. The commission's report concluded that, under documents signed by Putin and his deputy, more than $100 million worth of commodities were exported at prices far below market value, while foodstuffs were purchased at prices several times higher than the going rates.

The commission’s recommendations that Putin and his deputy, Aleksandr Anikin, be removed were ignored. Instead, Putin was granted additional authority. He has repeatedly denied allegations of corruption in the committee's work.

Many figures associated with the committee went on to have notable careers under Putin. In addition to Churov, they include former President Dmitry Medvedev, former Finance Minister Aleksei Kudrin, Gazprom CEO Aleksei Miller, Rosneft CEO and former Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin, and former Prime Minister Viktor Zubkov.