N/A

Select an inline link to view its contents.

In September 2022, as Ukraine was pushing Russian troops out of the eastern Kharkiv region, several Russian mercenaries were cut off from their main group after Kyiv’s forces recaptured the town of Balaklia.

For more than two weeks, these fighters hid in empty homes as they attempted to make it to the Russian side of the front line east of Balaklia. At some point during their flight, a member of their group took pen to paper and wrote a desperate note.

“Dear God, help us to return home alive and healthy. We are tired of wandering behind enemy lines for 15 days, thrown into defensive positions,” the note reads.

The trapped fighters were part of a battalion called the Wolves, one of numerous armed formations fighting for Russia’s invading forces under the umbrella of Redut, purportedly a private military company like Wagner, the mercenary group led by led by Yevgeny Prigozhin before his death in an August 23 plane crash.

But an investigation by Schemes and Systema – RFE/RL’s Ukrainian and Russian investigative units, respectively – revealed that Redut is not, in fact, a private military company. It is a front: a shadowy recruitment network run by the Russian military’s main intelligence directorate, known as the GRU.

Based on battlefield records and multiple interviews with Redut fighters and recruiters, the investigation provided an unprecedented look inside this secretive GRU program that at times resembles a hall of mirrors: contracts signed with nonexistent companies, fighters attached to military units on paper only, and in one case, a posthumous state award from Russian President Vladimir Putin for a Redut fighter of whom the Defense Ministry said it had no record.

Now, RFE/RL is publishing additional records, testimony, and independent reporting by Schemes and Systema revealing the inner workings of this system, which Redut recruiters say offers multiple benefits for those who sign up – including the option to quit without the threat of a court-martial and the ability to earn cash that can be hidden from creditors, courts, and the government.

Redut was created “so that people could avoid paying taxes or, for example, any court costs,” one recruiter told Systema.

This arrangement also allows the Russian government and military to maintain a layer of legal distance from the many fighters and units under the umbrella of this ostensibly private organization.

“Russia has faced big challenges with recruiting and retention because of the available pool of potential recruits being very low,” Candace Rondeaux, a researcher at the New America Foundation in Washington and the author of a 2019 report titled Decoding The Wagner Group, told RFE/RL. “And because of the culture of the military and the benefits that it offers, it just isn't incentive enough to get people to sign up voluntarily.”

“So these kinds of ghost forces or backfill forces, like we've seen with Wagner or Redut, are necessary because it essentially is a means of creating incentives outside the current system,” Rondeaux added.

Neither the Russian Defense Ministry nor Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov responded to written inquiries about Redut.

But in the Redut system, all roads lead back to Russian military intelligence, the Schemes and Systema investigation found.

The note left by the trapped Russian fighters in Balaklia in September 2022 was just one of a cache of documents left behind by the Redut-linked Wolves battalion. A few months later, four Wolves fighters who were captured by Ukrainian forces – Ruslan Kolesnikov, Mikhail Ivanov, Maksim Volvak, and Valentin Bych – were convicted of torturing civilians and sentenced to prison.

Written in block letters in the bottom left-hand corner of the note was a three-letter acronym: GRU.

At the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ivanov and his fellow fighters with the Wolves were deployed in the Kremlin operation to seize Kyiv. When it failed a few weeks later, they were ordered to cover the withdrawal of regular Russian troops from the region around the Ukrainian capital.

On April 1, their battalion was ordered to retreat to Belarus and then to a base in the town of Valuyki, near the Ukrainian border in western Russia.

Wolves’ Movements In Russia’s War On Ukraine: A Map

The following September, Ivanov and his fellow mercenaries were deployed to the Kharkiv region to fight Ukraine’s liberation effort in the area. They were two weeks into the mission when, fearing they had been abandoned by the retreating Russian military, a battalion member wrote the note pleading for help that was left behind and later obtained by Schemes.

Wolves fighters in Balaklia

Over the previous weeks, the Ukrainian military had recaptured Balaklia, where evidence of torture by Russian occupying forces was uncovered in the wake of their withdrawal.

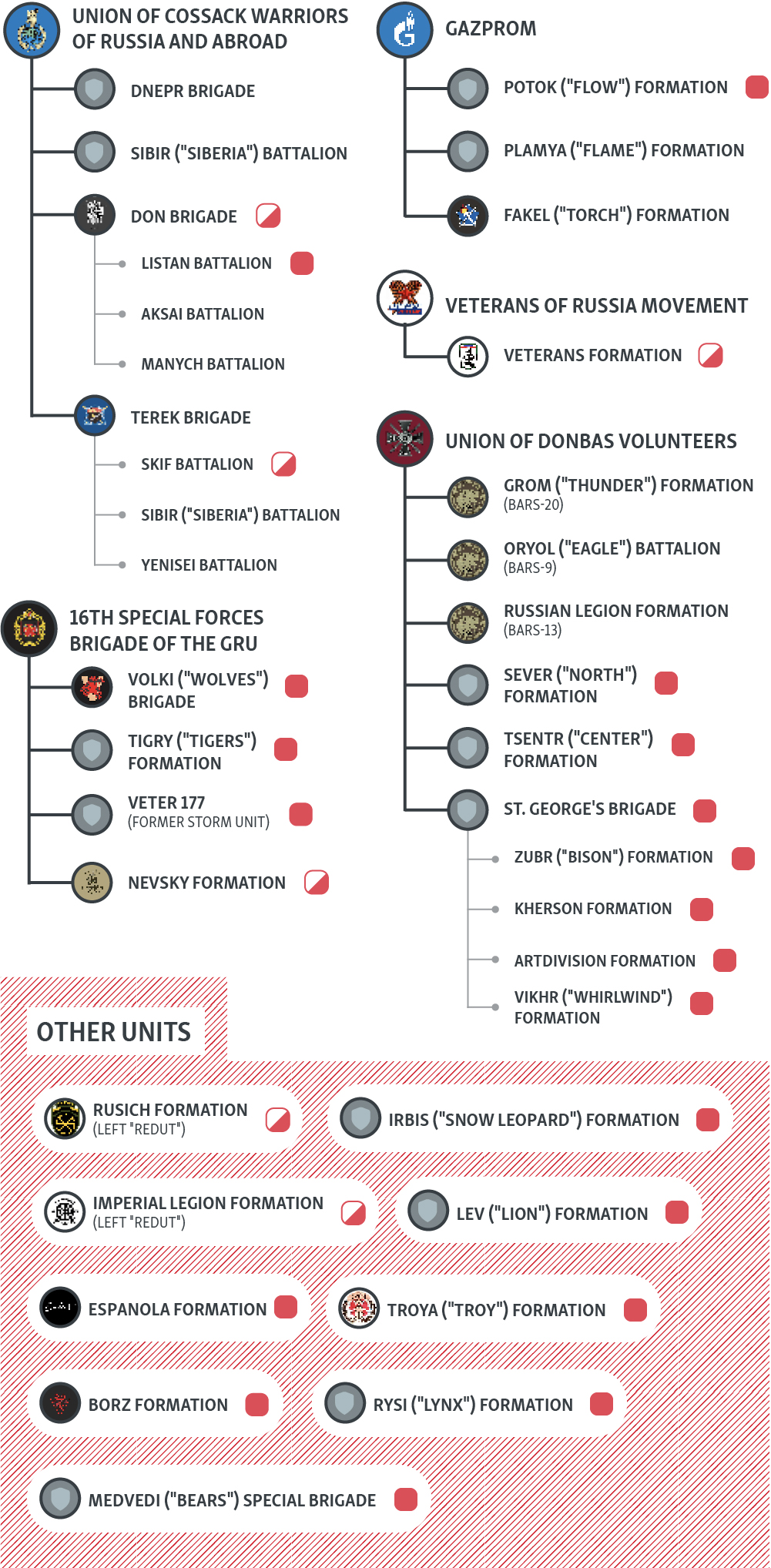

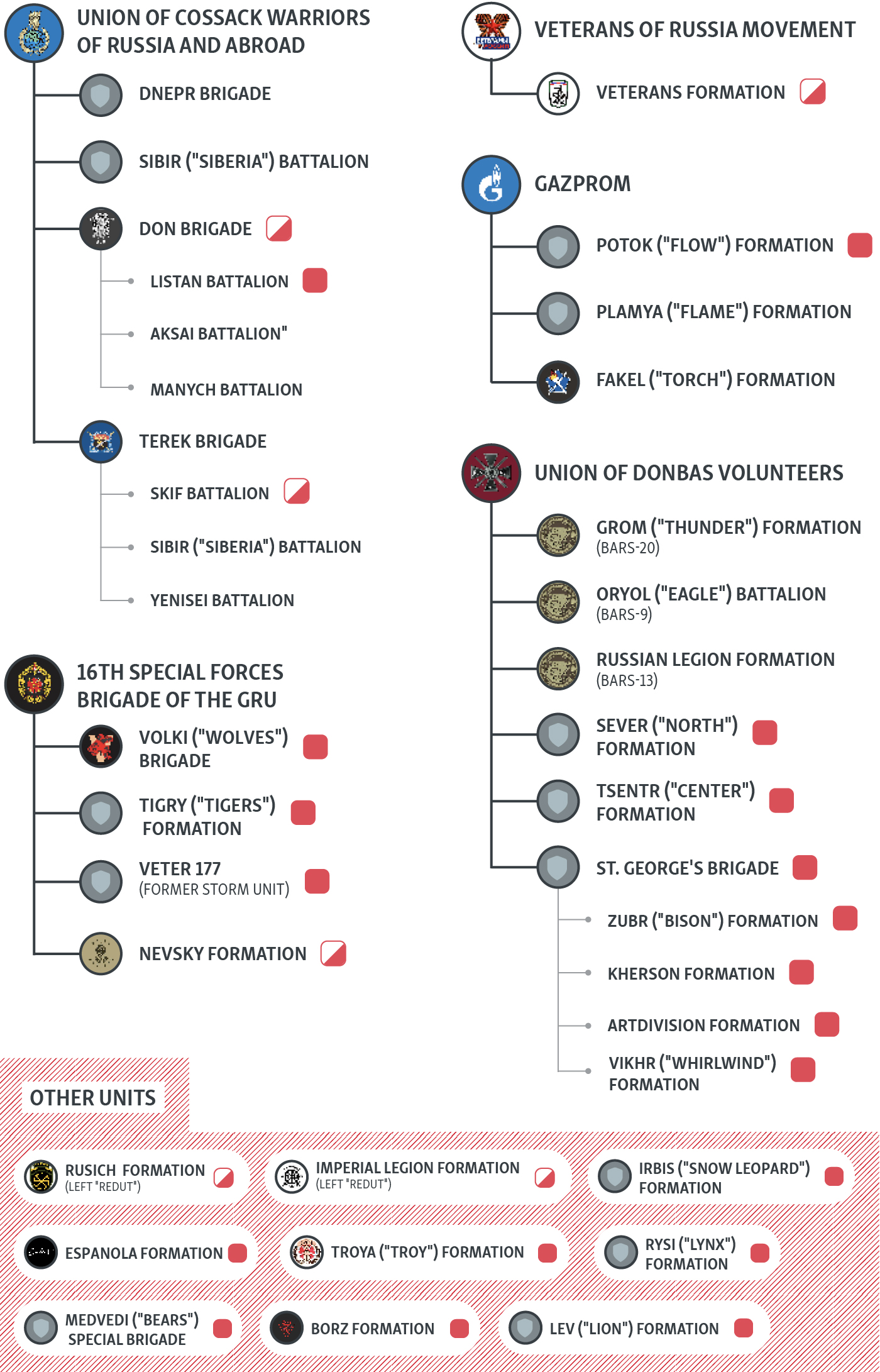

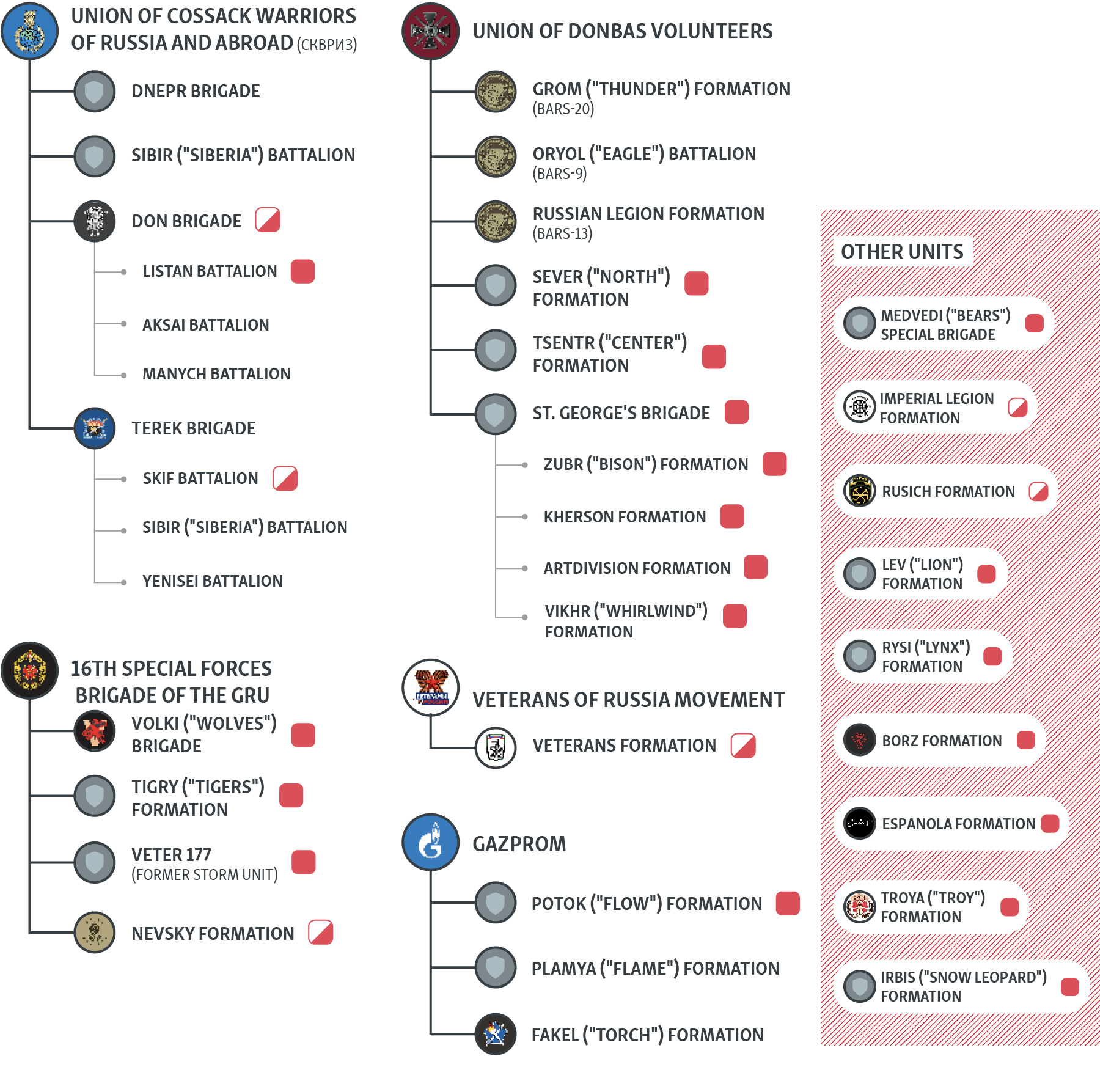

The Wolves, who are also known as the Lapwing battalion, are one of at least 20 armed units operating in Ukraine under the Redut network, according to an RFE/RL analysis of open-source records and interviews with recruiters and fighters.

Russian Armed Formations With Ties To Redut

Systema, RFE/RL Graphics

Convicted Wolves fighter Mikhail Ivanov on signing up with Redut

But in fact, the company Ivanov believed he had signed his contract with does not exist. It was a fictitious firm used as part of the Redut recruitment operation run by the GRU.

Two of Ivanov’s fellow fighters told Schemes that the battalion was directly overseen by a GRU officer. Several battalion members said this handler used the call sign Amur and gave the orders to hold multiple local men in the Kharkiv region village of Borova captive in an earthen pit for interrogations – including at least one in which he wielded a knife and threatened to cut off a captive’s fingers, according to a Ukrainian court verdict.

The Wolves battalion’s connections to the GRU, the military intelligence directorate linked to the poisonings of Kremlin targets and sabotage operations in Europe, don’t end there.

In both their trial testimony in Ukrainian court and in interviews with Schemes following their convictions on torture charges, two battalion members said they signed up with the GRU’s 16th Special Forces Brigade.

Internal records from the battalion also show that it was identified as part of the GRU.

How Redut’s Wolves Battalion Calls Itself Part Of The GRU

A typed report on the Wolves personnel losses identifies the formation as part of the GRU.

A handwritten report on casualties identifying the Wolves as part of the GRU

A handwritten report on casualties within a Wolves unit describes the battalion as part of the GRU.

The Wolves also use the training facility of the GRU’s 16th Special Forces Brigade in the Tambov region, according to photographs obtained by reporters and interviews with fighters. The facility is where Wolves fighter Ivanov says he stayed briefly in December 2021 – less than three months before Russia’s full-scale invasion – before being sent almost immediately to Russian-controlled territory in Ukraine’s eastern Luhansk region.

It was in Luhansk, Ivanov said, that he signed his contract with “some kind of Redut LLC.”

“We arrived [December] 9, and on the 10th they handed us contracts and [said]: ‘Read it, sign it,’” Ivanov told Schemes.

The Redut Mirage

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, several media reports have connected Redut to Redut-Security, a Moscow-based private security company that had previously guarded Russian energy facilities in Syria and was even targeted with sanctions by the U.S. government, which described it as a GRU-linked “private military company” that “is fighting in Ukraine.”

The owner of Redut-Security is Yevgeny Sidorov, a former Russian mercenary in Syria and a business associate of Konstantin Mirzayants, a special forces officer with the Russian air force. The Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta previously identified Mirzayants as the leader of a mercenary group involved in guarding energy assets in Syria controlled by Kremlin-connected billionaire Gennady Timchenko. Timchenko, who did not respond to a request for comment, has been linked to Redut in media reports and anonymous testimony in the British parliament.

But RFE/RL’s investigation found no evidence that either Redut-Security or Timchenko is linked to the Redut forces deployed in Ukraine following the full-scale invasion, which appear to have begun to take shape sometime in late 2021.

One contract reviewed by RFE/RL, which features the name RLSPI Redut, directly points to an affiliation with Russian military intelligence.

A CV posted on a Russian job site spells this acronym out as “Regional Laboratory of Social and Psychological Research” and links it to military unit No. 35555, part of the GRU’s 78th Intelligence Center, which is associated with the 175th Command and Communications Brigade based outside Rostov-on-Don, a regional seat near the Ukrainian border. The resume describes the unit as “secret.”

Public information about this military unit is scarce, but the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) has previously listed it as part of Russian military intelligence. Members of a Russian social-media page dedicated to unit 35555 regularly post images celebrating Russian military intelligence, while one user of the social-network VK describes himself as a veteran of “[military unit] 35555 GRU.”

The sheer number of Russian firms using the name Redut likely helps the fake companies listed on the fighters’ contracts fly under the radar. At least 180 LLCs with the name Redut have been registered in Russia, more than three dozen of which are currently active, according to the Russian commercial registry.

A search of Russian public records by Systema found nearly 50 people named Igor Ivanovich Shirokov – the name listed as the Redut head on multiple contracts signed by fighters. Reporters found no links between any of these individuals and a registered legal entity that included the name Redut.

The legal mirage of this purported “private military company” has made it difficult for relatives of Redut mercenaries to track down those in charge to ask about unpaid wages, death benefits, fighters’ whereabouts, leading to exasperated posts on Russian social-media networks.

Social-Media Posts From Mercenaries’ Relatives Searching For Redut

There are no publicly available contact numbers for the various armed units operating under the Redut brand in Ukraine. In conversations with Systema, recruiters for these units said no such numbers exist and that families should just call them.

The widow of one Redut fighter told Systema she’d been through “seven circles of hell” trying to collect back wages for her husband after he was killed in action.

Exclusive documents obtained by Systema highlight the murky, off-the-books nature of the Russian forces fighting in Ukraine under the Redut banner.

Among the cache of records left behind by the Wolves and later obtained by Schemes include mentions of battalion fighter Aleksandr Kopyltsov, a sniper using the call sign Nemo who was killed in battle in late March 2022 near Kyiv.

Kopyltsov’s relatives subsequently attempted to receive death benefits from the Russian government but hit repeated roadblocks. They received at least five letters from the Russian Defense Ministry and military prosecutors saying there was no record that he had fought under Defense Ministry forces or “volunteer” groups in Ukraine.

While the Defense Ministry and military prosecutors may have had no record of Kopyltsov, the Kremlin apparently did: Putin posthumously granted him the Order of Courage in November 2022 – even before his family received multiple official letters saying the Defense Ministry was unaware of his combat in Ukraine.

Russian military prosecutors ultimately informed Kopyltsov’s family in July 2023 that it had already received compensation weeks after his death from “the private military company Redut,” and that because he had not fought under the Defense Ministry or a “volunteer organization,” there were no grounds to pursue action for the Russian government’s failure to pay death benefits.

That reference is the only official mention by Russian authorities of a purported private military group called Redut that RFE/RL reporters were able to find.

A response by Russian military prosecutors to an inquiry about Aleksandr Kopyltsov states his death benefits were paid by the “private military company Redut.”

(Courtesy photo)

It remains unclear exactly how the Russian government would have learned of a payout to the family from Redut if it had no record of Kopyltsov as either a Russian soldier or volunteer.

But according to multiple Redut recruiters with whom Systema spoke, the paymasters of this purported private force are the Russian Defense Ministry itself – and its operators, the GRU.

"The majority of those fighting for what journalists call ‘private military companies’ are simply soldiers fighting under the control of the Defense Ministry," one source close to the GRU told Systema when asked about Redut.

While Russian military prosecutors have called Redut a private military company, the recruiters who find people to fight under the Redut auspices confirm that no such company exists. In fact, there is no such legal category as “private military company” in Russia, although the appellation is regularly used for Wagner and the other mercenary groups supporting the Russian military.

In order to find out what ordinary Russians could learn about the ostensibly private Redut units fighting in Ukraine, Systema reporters contacted 11 different recruiters for Redut-linked battalions involved in the war. Five stated explicitly that the Russian Defense Ministry and the GRU are behind the operation of the Redut system.

“The Redut system – it’s, well, GRU,” Natalya Lashkaryova, a senior member of a group called the Union of Donbas Volunteers, a semiofficial Russian organization recruiting fighters for the war in Ukraine, told a Systema reporter who called posing as a recruit.

Another recruiter, who uses the call sign Gonyets (Messenger), said that while those who enlist sign contracts with Redut, “we are working with the Defense Ministry, the Main Intelligence Directorate. They pay us the money.”

Recruiters On Redut’s Links To The GRU And Russian Defense Ministry

Gonyets (“Messenger”), Tigers Battalion Recruiter:

"This contract is specifically with Redut. We are working with the Defense Ministry, with the Main Intelligence Directorate. They pay us the money." "[Redut] is an analogue of a [Private Military Group]. We receive money from the Defense Ministry. Directly. Our handler is from the Defense Ministry."

Nadezhda Lashkaryova, Union of Donbass Volunteers, Head of Personnel:

"The Redut system – it’s, well, GRU."

Igrok (“Player”), Redut-linked Lynx Formation Recruiter:

"The contract is with a private company, but the [Russian] Defense Ministry pays. All of the payments come from them."

Zodiac, recruiter for Union of Donbass Volunteers battalions:

"Redut is a [private military company], but under the patronage of the Defense Ministry."

Jamal, Recruiter For Redut-Linked Battalion Veter 177:

"Ours is Veter 177. This is a unit that is part of the GRU’s 16th brigade. We are part of this exact brigade. We do intelligence. We don’t do assaults."

In chats with Systema reporters on Telegram, two other Redut recruiters said fighters would receive payment and support from the Russian Defense Ministry and the GRU. One of the recruiters, using the call sign Djamal, called Redut a “fake company.”

The amount of money recruiters promise potential recruits for enlisting is roughly the same: 110,000 rubles ($1,100) a month for time spent training and 220,000 rubles ($2,200) a month for time spent fighting in Ukraine. Thе salary for fighting is around three times the average monthly salary in Russia. Recruits are also promised large payments in the event of injury or death.

Redut contracts, as well as interviews with Wolves mercenaries and their relatives, indicate that Redut mercenaries are paid in cash.

Mikhail Ivanov, the Wolves mercenary who was taken prisoner and agreed to speak to Schemes following his conviction on torture charges in Ukraine, said the cash is brought to the front – in U.S. dollars – by the unit commander.

Paying The Redut-linked Wolves Battalion

An image from the phone of a fighter with the Wolves, whose members receive payments in U.S. dollars.

A contract to join the Wolves specifies a $25,000 payout for serious injuries and a $60,000 payout in the event of death.

A spreadsheet of Wolves battalion members shows their salaries listed in U.S. dollars.

As of early 2023, fighters in some Redut units received money at the base of the 150th Motorized Infantry Division in the Rostov region, a source told Systema.

For potential mercenaries, a contract under a system like Redut offers better conditions than signing up with the military. The contracts last from three to six months, and if a fighter decides to go home early, the worst that usually happens is that they lose some of their pay and are blacklisted by their Redut unit. By contrast, soldiers in the military are required to serve until the end of what Russia calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine and, in the event they go AWOL, they could face years in prison.

The recruiter Djamal said fighters are signed up via the Redut system so they can avoid debt-collectors, legal garnishments, and alimony payments -- and so they have the option to quit before getting thrown into “a long meat-grinder with no way out.”

It’s unclear whether commanders have a formal accounting system for the money passing through this black-box operation.

After the dramatic but short-lived mutiny by Prigozhin’s Wagner forces in June, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu ordered all mercenaries to sign contracts with his ministry by July 1. However, a recruiter with the call sign Kesha said that as of midsummer, only commanders were being pressed to do so, while rank-and-file fighters continued to fight “unofficially.”

Kesha is a recruiter for the Zubr (Bison) battalion, one of at least 20 armed mercenary groups that RFE/RL has identified as fighting in Ukraine as part of the Redut system.

Some of the groups are based at the Trigulyai training and mustering center outside Tambov, which is the home of the GRU’s 16th Brigade. These include one, called Alexander Nevsky, that calls itself a Russian Orthodox, patriotic formation, as well as several units named after animals – the Wolves, Tigers, and Lynx.

Because of the large number and varying sizes of these groups, it is difficult to estimate the total number of Redut mercenaries in Ukraine. The recruiter Kesha estimated the size of the Redut network at up to 25,000 fighters.

Sources – including Redut fighters interviewed by RFE/RL – indicate that recruitment under the Redut system began in the second half of 2021.

Ivanov, the Wolves battalion fighter who was convicted of torture after being captured in Ukraine, told Schemes that he signed up in December 2021 after hearing about the opportunity from a friend.

Fighters With The Redut-Linked Wolves Battalion Convicted Of Torture in Ukraine

Maksim Volvak

Ruslan Kolesnikov

Mikhail Ivanov

Valentin Bych

On December 9, 2021, Ivanov arrived at the gathering point for recruits near the Megamag shopping center in Rostov-on-Don. There, he says, he and around 80 others boarded minibuses and traveled to the Transpele base in the Russian-occupied part of Ukraine’s Luhansk region. It was there that Ivanov signed his contract with the fictitious Redut company for a monthly salary of $2,000, plus combat bonuses and benefits for injury and death.

Would-be Redut mercenaries can call or message a number listed on the ads, and the demands of the Redut recruiters on the other end vary depending on which formation is involved. A recruiter from a formation called the Veterans only asks a recruit’s age and immediately relays the address of the mustering point.

By contrast, recruiters for the Wolves battalion -- in which Ivanov fought -- require a full name and date of birth, a driver’s license, and background on a potential fighter’s military and civilian skills. Wolves recruiters also often ask about a prospective fighter’s criminal record and his health, although they usually do not demand medical documentation.

Recruits then assemble at the mustering centers and typically spend from a few days to a couple of weeks there. Many of the units gather at the GRU’s Trigulyai base outside of Tambov and are instructed to report to the base commander’s office.

Satellite Images Of The GRU’s Trigulyai Base

The soccer-hooligan unit known as Espanola has its mustering base in the Russian-occupied Ukrainian port city of Mariupol, in the Donetsk region. The Veterans, meanwhile, gather at a village in Russia’s western Belgorod region, which borders Ukraine. Units associated with the Union of Donbas Volunteers, including one called the St. George Brigade, are based in Rostov-on-Don and muster at a three-star hotel called Timosha on the left bank of the Don River.

After the recruits sign their contracts, the newly minted mercenaries are assigned to a military unit – often only on paper.

“We have a ‘virtual’ unit,” Gonyets, who recruits for the Tigers formation, told Systema. “If you end up in a hospital, you mention the number of your unit. When you arrive, they tell you what number to give in case something happens.”

Some people embrace the war.

People are different.

We try to avoid that.

We remove those who don’t fit,

those who are seeking to make profit,

those involved in dirty business.

I’ll tell you frankly about the Veterans unit: don’t even come close to them.

They work alongside us

but three of the groups they drafted

have already been killed.

People join them just to make money.

They have no other interest in it.

A recruiter with the Redut-linked battalion known as Wind 117 said those who sign up with the formation can receive “a certificate” from the GRU.

Systema also identified several military units associated with the Wolves battalion. Two of those units are under the GRU.

The Redut network does not have a single training ground or a unified training program. In Tambov, the mercenaries use the Trigulyai base, while in the Rostov region they have access to the Kadamovsky training base.

A Union of Donbas Volunteers recruiter told RFE/RL that their fighters use a training center in the Russian-occupied Ukrainian region of Crimea, although he did not name it.

Before they are sent into combat, the mercenaries are inspected by handlers from the Defense Ministry. Among other things, Kesha said, the handlers check the recruits for “the presence or absence of ties to neighboring governments,” meaning Ukraine.

When a mercenary’s six-month contract expires, he faces the choice of signing another Redut agreement or returning to civilian life. For those who return to Russia, it can be difficult to prove that they fought in Ukraine at all.

On February 4, 2023, the Union of Donbas Volunteers held a “congress” in Russian-occupied Mariupol, on the Azov Sea coast. More than 450 fighters, many of whom came “straight from the front,” participated in the event, according to Russian state media. It was seemingly the kind of run-of-the-mill uber-patriotic event that has become commonplace since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

But this gathering provided important insight into just who is running the Redut network of mercenary groups, which includes the Union of Donbas Volunteers.

The pro-Kremlin Telegram channel WarGonzo posted a video of the proceedings in which representatives of other mercenary companies could be seen. Those present included Aleksandr Borodai, a Russian lawmaker and former leader of Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine who heads the group, as well as Russian tycoon Konstantin Malofeyev and Aleksei Zhuravlyov, deputy chairman of the Defense Committee in the State Duma, Russia’s lower chamber of parliament.

During the gathering, organizers announced that all the volunteer militias were being concentrated into a single group called the Russian Volunteer Corps, an apparent attempt to bring order to the loosely connected formations.

Systema has obtained a document that was issued to a Redut fighter to confirm his participation in the “special military operation” in Ukraine. That document states that the Russian Volunteer Corps was created on February 27 “by order of the Defense Ministry of the Russian Federation.” It bears the stamp of the Defense Ministry.

Several recruiters contacted by Systema said that Redut -- not the Union of Donbas Volunteers -- served as the nucleus of the Russian Volunteer Corps. In fact, the Union of Donbas Volunteers itself is part of the Redut network. RFE/RL has established that fighters with the St. George Brigade sign contracts with Redut.

The document Systema obtained is signed by Colonel A. Kondratyev, who is identified as the “commander of the combat unit of the Volunteer Corps.” The signature belongs to Aleksei Kondratyev, a retired GRU colonel and a former mayor of the city of Tambov, which he also represented in the Russian parliament. The signature matches Kondratyev’s signatures found on publicly available parliamentary documents.

Kondratyev was one of at least three senior figures linked to the Russian Defense Ministry who were present at the February 2023 gathering of the Union of Donbas Volunteers.

The other two were Colonel Sergei Drozdov, a senior recruitment official with the General Staff of the Russian military, and Lieutenant General Vladimir Alekseyev, deputy head of the GRU.

Sources cited in a May 2023 joint report by The Insider, Germany’s Der Spiegel, and the open-source investigative group Bellingcat said that the idea of creating Redut belonged to Alekseyev, whom a Telegram channel linked to the late Prigozhin’s Wagner forces has called “one of the founders” of Wagner.

During Prigozhin’s murky mutiny in June 2023, Alekseyev released a video in which he called on the mercenaries to stop their “coup.” He was also one of the high-ranking Defense Ministry officials who held talks with Prigozhin in southern Russia during the mutiny.

Alekseyev disappeared from public view for several months following those negotiations with Prigozhin at the headquarters of Russia’s Southern Military District in Rostov-on-Don on June 24. On October 16, a video appeared on the Telegram channel of the Redut-linked detachment Espanola showing Alekseyev awarding one of the unit’s fighters with the Order of Courage.

Neither Alekseyev, nor Drozdov, nor Kondratyev responded to requests for comment, though Alekseyev marked the inquiry sent to his Telegram account with a heart emoji.

In August, Schemes reporters traveled to the front line near the devastated city of Bakhmut in the northeastern part of Ukraine’s Donetsk region. On the outskirts of the village of Orikhovo-Vasylivka, fighters with the Ukrainian Army’s 225th Separate Assault Battalion were conducting aerial reconnaissance of Russian positions.

Ukrainian forces have been battling invading Russian forces in the area for more than a year, and many collect chevrons worn by Russian soldiers they have captured or killed. Among the chevrons they showed reporters were those of the Veterans, one of the armed formations operating in Ukraine under the Redut umbrella.

One of the insignia used by the Veterans is a chevron featuring the visage of Vladimir Putin.

“They are made up of former policemen, former FSB officers, soldiers, national guardsman – that is, former security forces,” a Ukrainian military commander said of the Veterans.

He added that captured Russian fighters from the Veterans formation carry military-unit documents bearing the seal of the Russian Defense Ministry and “volunteer” certificates.

“Plus a contract for six months, which is automatically renewed after six months,” the Ukrainian soldier said.

The Veterans are not the only Redut formation fighting in and around Bakhmut, he said, reeling off a list of purported private military groups that he likened to a “zoo,” including the Lynx and the Tigers as well as the Alexander Nevsky formation.

Russian fighters from the Veterans formation began appearing in Bakhmut after Russia’s main assault on the city in August 2022, another Ukrainian soldier told Schemes. Russian forces took control of most of the city in May 2023, with Wagner mercenaries playing a key role, but fierce fighting continues in the suburbs.

“From here, it’s about 5-6 kilometers to the [Russian] positions,” one Ukrainian soldier told Schemes in August in Chasiv Yar, a few kilometers west of Bakhmut, “including those occupied by the private military company Redut.”

Watch the documentaries by Schemes and Systema

Ukrainian Version (now with English subtitles)

PROJECT CREDITS

This project is a collaboration between Schemes, RFE/RL's Ukrainian investigative unit, and Systema, RFE/RL’s Russian investigative unit.

Authors: Yelizaveta Surnacheva, Daniil Belovodyev, Valeriya Yegoshyna, Kira Tolstyakova, Robert Coalson, and Carl Schreck

Contributing reporters: Dmitry Sukharev, Kirill Kruglikov, and Olha Ivlieva

Editing: Steve Gutterman, Carl Schreck, Andrei Soshnikov, Kira Tolstyakova, Natalya Sedletska, and Anna Peterimova

Design: Wojtek Grojec, Ivan Gutterman, and Juan Carlos Herrera Martinez